[rating=4] Charles Gounod’s Faust is something unusual: an opera with several parts you can tap your foot to. Granted, those parts may be the devil’s hymn to the golden calf or a woman’s delight at finding jewelry that is probably cursed, but it’s still a sprightly score. Now closing the Lyric Opera’s season is the premiere of a new co-production with Portland Opera. Directed by Kevin Newbury and with animator and sculptor John Frame as the lead designer, it makes use of the Lyric’s new technical capabilities to layer two visual universes on top of each other. One is that of the singing actors, who are all in top form. The other is of grotesque puppets and projections which frame the action. Though somewhat confusing and disorientating, it’s undeniably a rich experience.

[rating=4] Charles Gounod’s Faust is something unusual: an opera with several parts you can tap your foot to. Granted, those parts may be the devil’s hymn to the golden calf or a woman’s delight at finding jewelry that is probably cursed, but it’s still a sprightly score. Now closing the Lyric Opera’s season is the premiere of a new co-production with Portland Opera. Directed by Kevin Newbury and with animator and sculptor John Frame as the lead designer, it makes use of the Lyric’s new technical capabilities to layer two visual universes on top of each other. One is that of the singing actors, who are all in top form. The other is of grotesque puppets and projections which frame the action. Though somewhat confusing and disorientating, it’s undeniably a rich experience.

Faust (Benjamin Bernheim) is an elderly artist and scientist who is haunted by dreams of death and decay. We see his mental landscape in the projections designed by David Adam Moore—everything Faust imagines rots and becomes ugly. When he crawls out of bed to curse the new day, it’s obvious from looking at him that he smells like piss. Driven to furious jealousy at the sound of others enjoying spring, he contemplates suicide, but instead summons the devil, Méphistophélès (Christian Van Horn). Faust orders the devil to make him youthful again, and Méphistophélès proposes that he seduce a young woman, Marguerite (Ailyn Pérez, with Ana María Martínez taking over the role on March 21). Faust convinces himself that he loves her, but still abandons her at the demon’s urging, leaving an emotionally battered woman pregnant in a judgmental society.

This is the French tenor Bernheim’s American debut, and he’s remarkable not only for his vocal timbre, but also his willingness to put such an unsympathetic spin on his character. Gounod’s Doctor Faustus is closer to Marlowe’s jerkass than Goethe’s Byronic hero, and Newbury and Frame’s concept for him is that Méphistophélès is, in fact, his own creation and alter ego. This means that Van Horn’s Méphistophélès has all the charisma and self-confidence, while Faust is full of self-loathing and self-deception. During his first aria as the elderly doctor (“Rien! En vain j’interroge”), Bernheim’s voice has a plaintiff quality as he shakes his vial-clenching fist at a cloud. When he first encounters Marguerite’s brother, Valentin (Edward Parks) after regaining his youth, Faust experiments with copying Valentin’s movements and bearing. Above the stage looms a puppet representation of Faust with a telescope or microscope permanently before its eye, acting as a barrier between itself and the world. That Bernheim is a native French-speaker supplies Faust with one unexpected redeeming feature: his delivery of librettist Jules Barbier’s poetry is sublime.

Van Horn is a delight. His antics are a source of great amusement in the first act and there’s a swagger in his baritone voice as well as his shoulders. Set and costume designer Vita Tzykun has clad him in an yellow-orange plaid suit, and he has the nerve to introduce himself by asking if his appearance is pleasing. He hilariously finds himself in a tryst with Marthe (Jill Grove), Marguerite’s more distinguished neighbor and his P.T. Barnumesque charisma gets the townsfolk to enjoy being insulted by him. But he becomes more sinister over the course of the show, using his dark magic to lower Marguerite’s resistance to Faust’s advances and delighting in the abuse being heaped upon her. By the time he is tormenting her with visions of hell, he’s not funny at all, but is a gigantic, imposing figure.

Pérez, as Marguerite, is an ideal scene partner for the other actors, matching and passing back their energy during the show’s many rousing duets and trios. In short succession in Act II, she delivers the Jewel Song, which is giddy and avian, and a fairytale lullaby that is haunting and mournful. Chameleon-like, she adapts to both. The directors have imagined Marguerite as disabled, perhaps to compare and contrast her delight at erotic attention with the elderly Faust’s, but if so, it’s a subtle theme. Nonetheless, her spiritual struggle eventually overtakes Faust’s as the dramatic focus. As her brother, Edward Parks is an annoying but sincere conservative soldier-type, until he cruelly denounces her with the aria “Ecoute-moi bien Marguerite,” which is no less savage for its beauty.

The scenic concept, with all its stop-motion animated puppets, gamboling dancers in demonic masks, and presentation of multiple perspectives on the same buildings, makes for some complicated stage pictures. This is not, perhaps, an ideal introduction to the Faust story, although Barbier and Michel Carré’s script elided a lot, anyway. When it works, such as when cartoon scenes of cavorting skeletons frame the soldiers’ chorus, it works very  well, but there are also times when it competes with the actors instead of complementing them, and an audience member just has to pick which layer to look at. However, thanks to the quality of the singing and of the orchestra, conducted by Emmanuel Villaume, both layers have a vibrant soundscape to play off. The fast pacing of the music causes the three and a half hour run time to fly by, and by alternating scenes in which the live action or the animation are the focus, each aspect stays fresh.

well, but there are also times when it competes with the actors instead of complementing them, and an audience member just has to pick which layer to look at. However, thanks to the quality of the singing and of the orchestra, conducted by Emmanuel Villaume, both layers have a vibrant soundscape to play off. The fast pacing of the music causes the three and a half hour run time to fly by, and by alternating scenes in which the live action or the animation are the focus, each aspect stays fresh.

Faust will continue at the Civic Opera House, 20 N Upper Wacker Drive, Chicago, thru March 21, with the following showtimes:

March 9: 7:30 pm

March 12: 7:30 pm

March 15: 7:30 pm

March 18: 2:00 pm

March 21: 2:00 pm

Running time is three hours and thirty-five minutes with two intermissions.

The Lyric offers parking deals with Poetry Garage at 201 W Madison St. if inquired about in advance. Tickets are $17-319; to order, visit LyricOpera.org or call 321-827-5600.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Faust.”

More Stories

“Barefoot in the Park”

“Joe Turner’s Come and Gone”

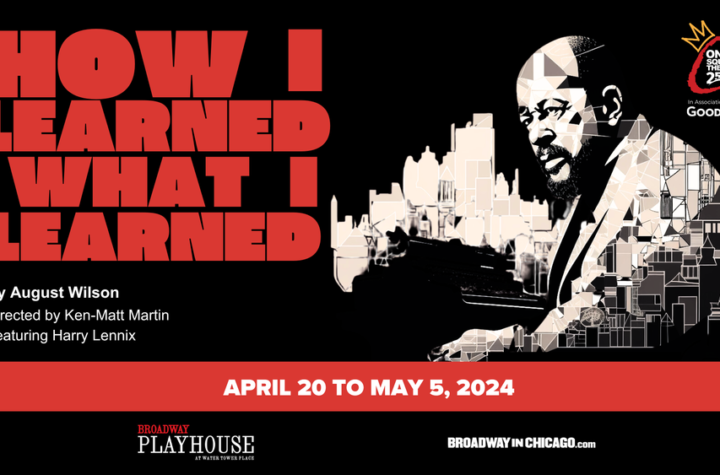

“How I Learned What I Learned” reviewed by Julia W. Rath