***** Giuseppe Verdi’s 1871 opera Aida is famous for being one of the most mature works of one of the most popular and prolific opera composers. It contains sophisticated uses of all the devices Verdi had developed over a career of several decades and, being commissioned by the Egyptian monarch, budget was no object. Essentially, Verdi was given the freedom to do almost anything he wanted and had the skill to do it. But what interested Francesca Zambello, the director of the new-to-Chicago production at the Lyric, was how Aida alternates between the characters’ interior struggles and the performances they put on during public state events. The story concerns conflicted loyalties during war and love, something people can always connect to, here presented with spectacle that is carefully crafted by artistic designer RETNA to support the personal emotional stakes of the story instead of competing against them.

***** Giuseppe Verdi’s 1871 opera Aida is famous for being one of the most mature works of one of the most popular and prolific opera composers. It contains sophisticated uses of all the devices Verdi had developed over a career of several decades and, being commissioned by the Egyptian monarch, budget was no object. Essentially, Verdi was given the freedom to do almost anything he wanted and had the skill to do it. But what interested Francesca Zambello, the director of the new-to-Chicago production at the Lyric, was how Aida alternates between the characters’ interior struggles and the performances they put on during public state events. The story concerns conflicted loyalties during war and love, something people can always connect to, here presented with spectacle that is carefully crafted by artistic designer RETNA to support the personal emotional stakes of the story instead of competing against them.

Aida takes place in ancient Egypt, which is at war with Ethiopia and has been off-and-on for some time. The titular character (soprano Michelle Bradley) is an Ethiopian princess who was taken captive early in life and given as a slave-in-waiting to the Egyptian princess, Amneris (mezzo Jamie Barton). At this point, Aida deeply cherishes her memories of her homeland, but they are fading, and she is much closer to Egyptian people than she is to other Ethiopians. She is even in love with Radamès (tenor Russell Thomas), an up-and-coming officer who is given command of the defense forces when the Ethiopians launch a sudden incursion that threatens the Egyptian capital. Radamès loves Aida back, but Amneris loves Radamès too, and everything in this rivalry seems stacked in her favor. But unbeknownst to the Egyptians, after Radamès’s victory, Aida recognizes one of the captives as her father, the Ethiopian king Amonasro (baritone Reginald Smith, Jr.), and her conflicted loyalties are no longer an abstract problem.

Zambello’s production establishes high stakes early on when the chorus of Egyptians responds to the Ethiopian encroachment with fury born of terror for their lives. For an enemy army to be within striking distance of their capital is a major disaster, after all, and the position of their high priest, Ramfis (bass Önay Köse), is elevated by their desperation. He plays a critical role by re-establishing order and acting as a fatherly figure to Radamès, from what we see from their brief interactions. The religious ritual prior to the off-stage battle is when we first see how Zambello and RETNA handle the opera’s spectacle interludes, which are tricky since they establish atmosphere but tend to pause the plot. The solution they’ve found is to use dance, choreographed by Jessica Lang, visuals inspired by cursive hieroglyphics, and the solemnity of the chorus to invoke a trance-inducing feeling of mystery and elegance. The state’s religious rituals feel extremely weighty even without hundreds of people or tons of heavy machinery needing to be onstage, something that remains true during the famous triumphal scene after the Egyptians were victorious but took heavy losses and were nearly destroyed.

The Lyric’s new music director, Enrique Mazzola, is particularly experienced with Verdi operas, and is the conductor for this production (except for the final two performances, which will be conducted by Francesco Milioto). As Verdi is so frequently featured at the Lyric, long-time attendees will recognize many of his themes in Aida, which in this late-career work fully came into themselves. There’s the chorus of cautiously hopeful patriots, the display of the state’s dread grandeur, the vengeful parent in a duet with a reluctant child, and even the heroine who found her strength at the last minute, all done with a defter hand than some of their earlier versions. There’s also a desperate old-fashioned plot contrivance built around a secret listener lurking by chance behind some scenery, although the emotional conflict is simple enough to not suffer much for that. All the actors are masterful at selling a feeling; Aida has very little freedom to act, but Michelle Bradley plays her by putting rich sensitivity and turmoil into her powerful voice. Russel Thomas’s Radamès is charming and earnest enough to get some appreciative chuckles from the audience and shows himself to be a good-hearted hero off the battlefield as well as on it, and Jamie Barton’s Amneris undergoes a redemption arc in which we see the character mature before our eyes into a ruler who might bring peace after the story’s tragic conclusion.

Like any play that’s been consistently popular for a long time, Aida has acquired a lot of metatext that’s hard to completely shake for a viewer or a creator. The show’s 1871 premiere was delayed by the Franco-Prussian War, and endless rivalry between equally matched, culturally similar countries was the lens through which it was interpreted early on, but Italy’s later invasions of Ethiopia have long hung over it. Costume designer Anita Yavich gives the show a timeless feel by mixing costumes that look like they could be from the early twentieth century with garb that could be inspired by ancient clothing. It makes for a unique stage picture, but the ancient Egyptians did maintain design elements of their state religion for a very long time, and Cleopatra is closer on the timeline to us than she is to the Old Kingdom. Michael Yeargan’s set design features a bunker that is oppressive and ominous, yet paradoxically a place of safety during invasion, neatly encapsulating the pressures of conflict that even elites feel is out of their control. Part of the reason for Aida’s enduring popularity is that it is an easy entry-point for opera, with knowledge of its history adding to it but not requiring anybody to look deeply into nineteenth century politics to enjoy it, and its dramatic sensibilities being near to contemporary tastes. The production at the Lyric does justice to a master at his best.

Aida will continue at the Lyric Opera House, 20 N Upper Wacker Drive, Chicago, thru April 7, with the following showtimes:

March 20: 7:00 pm

March 20: 7:00 pm

March 23: 7:30 pm

March 26: 7:00 pm

March 29: 7: 00 pm

April 1: 7:00 pm

April 4: 2:00 pm

April 7: 2:00 pm

Running time is three hours with one intermission. There is also a thirty-minute preview talk an hour before the show.

Performances are in Italian with supertitles.

Ticket prices start at $59. The Lyric offers parking deals with Poetry Garage at 201 W Madison St. if inquired about in advance. To order, visit LyricOpera.org or call 321-827-5600.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click “Aida.”

More Stories

“Barefoot in the Park”

“Joe Turner’s Come and Gone”

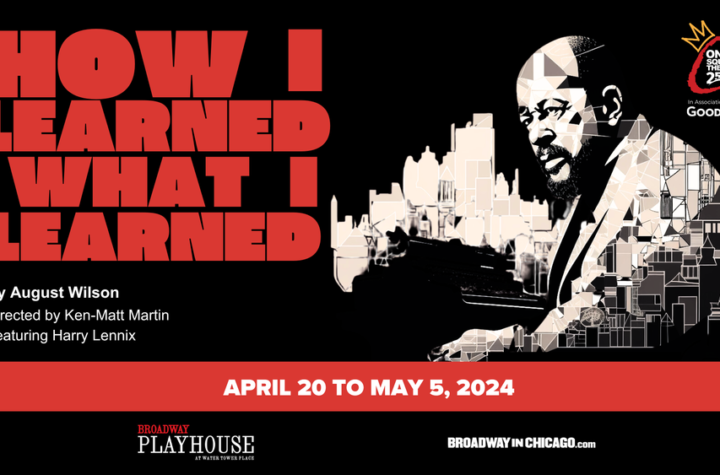

“How I Learned What I Learned” reviewed by Julia W. Rath