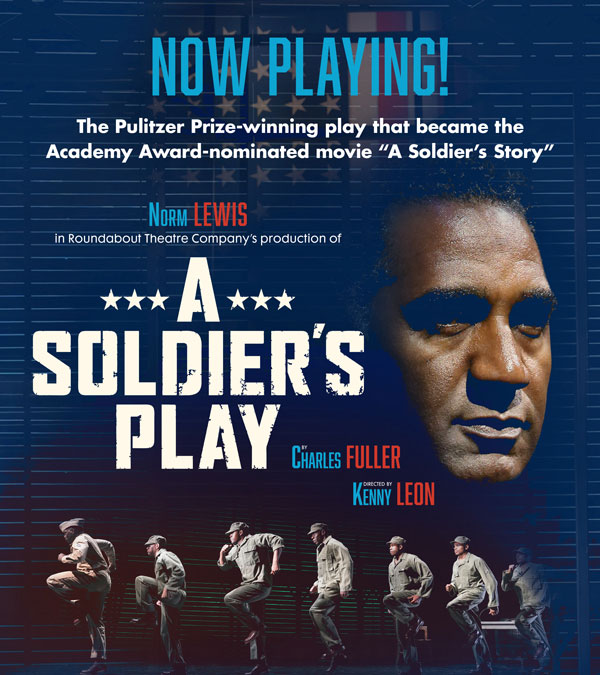

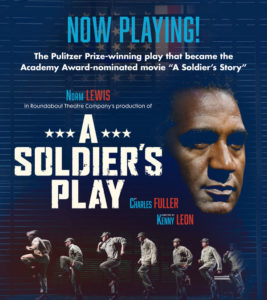

[rating=5]“A Soldier’s Play”, written by Charles Fuller, is a murder mystery set in the early 1940s at Fort Neal, Louisiana, a racially segregated army base that is home to black troops. Impressively directed by Kenny Leon, this play is as much about how African Americans perceive of differences among themselves, such as socioeconomic background, the region of the country that they come from, their place within the black social hierarchy, and their previous contact with whites. While the men don’t all get along, what they have in common is that they have to deal with racism and a Southern caste system where “Negroes and colored boys” are treated with contempt, if not outright hate, by the dominant white society. Not only are they stationed in an area of the country where the Ku Klux Klan is to be feared, but they always have to keep in mind certain cultural expectations of that era as to their subservience. They especially despise being treated as second-class citizens in the army and given menial jobs stateside. They would rather serve their country overseas and are anxious to fight Hitler and the Nazis in World War II.

[rating=5]“A Soldier’s Play”, written by Charles Fuller, is a murder mystery set in the early 1940s at Fort Neal, Louisiana, a racially segregated army base that is home to black troops. Impressively directed by Kenny Leon, this play is as much about how African Americans perceive of differences among themselves, such as socioeconomic background, the region of the country that they come from, their place within the black social hierarchy, and their previous contact with whites. While the men don’t all get along, what they have in common is that they have to deal with racism and a Southern caste system where “Negroes and colored boys” are treated with contempt, if not outright hate, by the dominant white society. Not only are they stationed in an area of the country where the Ku Klux Klan is to be feared, but they always have to keep in mind certain cultural expectations of that era as to their subservience. They especially despise being treated as second-class citizens in the army and given menial jobs stateside. They would rather serve their country overseas and are anxious to fight Hitler and the Nazis in World War II.

Then too, the soldiers have different skin tones, and this forms a major portion of the underlying story. Colorism, or color discrimination, can and does exist among some African Americans; it is often recognized as being part of the culture that can form the basis for unequal treatment within families. Although this show does not deal with familial prejudices, it does deal with something perhaps more insidious. To fully understand “A Soldier’s Play”, one has to know something about the history of the State of Louisiana, which was originally colonized by the French. There the Creoles of color were considered a separate caste since the days of slavery, making color discrimination an established institution. Whites would distinguish among blacks in accordance with the highly discriminatory “brown paper bag test.” Individuals who matched a brown paper bag or were lighter in color were traditionally considered of higher status and thus given more privileged positions. Consequently, in the time period when this play is set, the norm of colorism would have been entrenched and likely internalized not only among whites but among blacks. When the army base in “A Soldier’s Play” brings together African American soldiers from across the country, some men (but not all) are clued into this cultural history and what the various gradations of skin color mean in Louisiana.

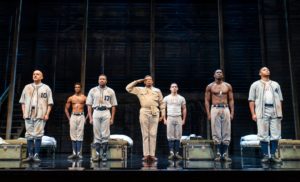

Within this milieu, Sergeant Vernon C. Waters, a light-skinned black man, is tasked with the responsibility of overseeing the segregated unit and uses its members to form a winning baseball team: an outgrowth of the Negro Leagues. Waters (in a splendid and convincing performance by Eugene Lee) acts the part of an Uncle Tom who wants to curry favor among whites. Much like the way that slave foremen, or slave drivers, were placed in a position of assisting their white overseers in the ante bellum South, Waters has been given power over these recruits to enforce discipline and do the bidding of the white man’s army. He buys into the structural racism of the institution by taking the initiative to weed out those black men who he considers to be the most ignorant, “down home”, or excessively servile—and in so doing, claims that he is doing the black race a favor. Waters, by all accounts, is cruel, and psychologically, he has trouble negotiating his role as a middleman between the white officers above him and the black soldiers under his command. And so he has turned to alcohol. It is during one of these episodes of self-hate, self-doubt, and weakness that Waters is murdered. Everybody hears two gunshots, but who is the killer? Could it be a Klan member or somebody else? And what could have been their motivation to shoot him?

Captain Richard Davenport (marvelously portrayed by Norm Lewis) is a black attorney and graduate of Howard University, who is assigned by the Judge Advocate General’s Corps to look into Sergeant Waters’ murder. This is unprecedented territory, and Captain Charles Taylor (William Connell), who is white, cannot believe that “a colored man” could have been put in charge of the case. He fears that the investigation might not be taken seriously enough and thus could be jeopardized; something that Taylor does not want to happen, since feels a great responsibility to his men. Although his fears are pragmatic ones in an era before the U.S. military was integrated under President Harry S Truman, the audience instinctively feels that the interaction between Davenport and Taylor is consciously or subconsciously racist from the perspective of our own time period. Nevertheless, cultural differences and misunderstandings between the two have to be worked out for the sake launching a credible investigation. That said, the black captain’s very presence breaks the glass ceiling regarding how high a black soldier can rise through the military ranks.

Davenport’s interviews with suspects and witnesses who have had some association with Sergeant Waters is reminiscent of the structure of Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Perry Mason.” The black troops who are questioned are made up of: Corporal Bernard Cobb (Will Adams), Private First Class Melvin Peterson (Alex Michael Givens), Private Louis Henson (Branden Davon Lindsay), Private James Wilkie (Howard W. Overshown), Private Tony Smalls (Malik Esoj Childs), and Private C.J. Memphis (Sheldon D. Brown, who sings and plays guitar wonderfully). Unlike Perry Mason, however, Davenport is constantly put off when he needs to cross the color line in order to interrogate white suspects. These include Lieutenant Byrd (Chattan Mayes Johnson) and Captain Wilcox (Matthew Goodrich). Last but not least, Corporal Ellis (Alex Michael Givens) works with Captain Taylor as his assistant.

The stark scenic design in this play is perfect, thanks to the fine work of Derek McLane! The unadorned horizontal and vertical lines throughout the set are reminiscent of the no-frills army life. Prop design couldn’t be any better, and the moveable items—from bunks to desks to coffins and even the tiny prison cell inhabited by C.J.—are ideally crafted, especially when the actors speed up the action by moving the props all around by themselves. This movement is not only efficient in shifting from one scene to the next but keeps the audience occupied; there is never a dull moment. Lighting by Allen Lee Hughes likewise demarcates scenes and is especially effective at the very beginning before the characters are introduced as well as throughout. Costume design by Dede Ayite is exactly what it should be, given the locale and time period. Kudos also must go to Dan Moses Schreier, the sound designer; Kate Wilson, the dialect coach; and Thomas Schall, the fight choreographer, who has trained the actors in remarkably realistic-looking physical violence.

Despite variations in the degree of bitterness that these black soldiers might feel about being in the army and about those in positions of authority, the overarching theme is that these men are more alike than different from each other. This is characterized by their knowledge of a common history as portrayed by similar interests in music. Lovingly done are the stirring African American spirituals and blues numbers sung by several of the characters. The songs are not just an authentic cultural expression but draw a parallel to the ante bellum South, when enslaved people sang songs to pass the time. This serves as a metaphor for the fact that the black men are still in bondage when they serve in the segregated U.S. Armed Forces in the 1940s. Yet it is the hook of the whodunnit which binds the characters of both races together as they resolve to find out who could have murdered Sergeant Waters and why they might have done so. In all, this is a fascinating tale, an excellent production, and a must see!

“A Soldier’s Play”, brought to us by Broadway in Chicago, is playing through April 16, 2023, at the CIBC Theatre, 18 W. Monroe Street, in Chicago.

Tickets start at $35.

Performance schedule:

Performance schedule:

Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays – 7:30 p.m.

Wednesdays – 2:00 and 7:30 p.m.

Saturdays – 2:00 and 8:00 p.m.

Sundays – 2:00 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. ( except on the 16th)

Additional performance: Sunday, April 9th at 7:30 p.m.

For more information and to purchase tickets, go to: https://www.broadwayinchicago.com/show/a-soldiers-play/.

For additional information about the North American tour, see: https://www.roundabouttheatre.org/get-tickets/2022-2023-season/a-soldiers-play-tour/.

Current COVID protocols at the CIBC Theatre: Masks are optional at this time. Advice is subject to change.

More Stories

“Survivors” reviewed by Julia W. Rath

“Prayer for the French Republic” reviewed by Julia W. Rath ( and another by Paul Lisnek)

“Obliteration” reviewed by Mark Reinecke