“The Ballad of Truman Capote” opens with him on the phone talking to Tallulah Bankhead in his suite at New York’s Plaza Hotel. Played by Patrick Moy, the one-man play takes place in the Plaza Hotel as Capote prepares for his “party of the century,” the famous Black-and-White ball on November 28, 1966, for select A-list celebrities.

“The Ballad of Truman Capote” opens with him on the phone talking to Tallulah Bankhead in his suite at New York’s Plaza Hotel. Played by Patrick Moy, the one-man play takes place in the Plaza Hotel as Capote prepares for his “party of the century,” the famous Black-and-White ball on November 28, 1966, for select A-list celebrities.

Not all celebrities are invited, such as actors and novelist Jacqueline Suzanne, whose writing he describes as “so bad it makes Gore Vidal look like Tolstoy.” Adding, “Valley of the Dolls ain’t coming to the ball.” His name-dropping includes Norman Mailer, William Baldwin, and Andy Warhol (who’s given permission to take photos).

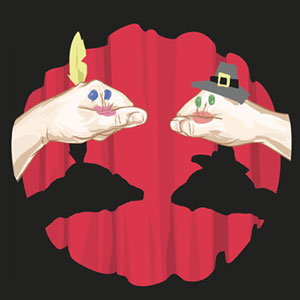

The script, considered a ballad, is written and directed by three-time Booker-nominated author Andrew O’Hagan. Moy has the unique voice of Capote and his mannerisms down pat as he continues to refill his martini glass while reminiscing about his childhood and career as a writer, not only getting drunker but also more maudlin. He’s asked the front desk to hold phone calls and no knocks on the door to deliver flowers so he can be alone.

The irony that Capote is hosting a masked ball reveals his own public mask hiding his loneliness, insecurity, and depression. In this play, the mask is removed for an hour, and we see Capote’s inner self, “a sweet boy from the South.” He says he wasn’t a real boy at all when born in New Orleans. At 10, he moves to New York to live with his mother in a hotel who lives in fantasies, an insight into how he lives and sees the world around him. He says he was “seldom in love, always in haste.”

Known for Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood, the novel “That Paid for This Ball,” he explores the isolation and cost of a writer in having to reveal a sense of evil that comes with human beings. He talks of how critics dismissed In Cold Blood of not being factual, when in fact it was. . .all but the ending, which was fact-checked by The New Yorker but not revealed.

While the play delves behind Capote’s mask, his quick wit that entertains his public provides levity in the play, which keeps the audience involved rather than turned off. In the end, I felt sorry that Capote could not enjoy his fame and success. “I regret I never put pen to paper. I may never write again.”

Moy parts the stage in the black mask he wears to the ball. Fittingly, lights go dark. As he said earlier in the play, “This is my swan song.”

More Stories

“The Prom” at Glenbrook High School

“The Simon & Garfunkel Story” comes to Chicago

Passover Dinner at Frank’s ( Italian style)