[rating=4]“Waiting for Godot” is funny, maybe. It’s sad, maybe. It’s not totally dark but is far from light. Above all, it’s deep, that is, when you get past the shallowness inherent in all the waiting. Nothing happens, yet everything happens. True to the original, this production plays it straight and literally by the book. If you like heady plays, this show is for you.

[rating=4]“Waiting for Godot” is funny, maybe. It’s sad, maybe. It’s not totally dark but is far from light. Above all, it’s deep, that is, when you get past the shallowness inherent in all the waiting. Nothing happens, yet everything happens. True to the original, this production plays it straight and literally by the book. If you like heady plays, this show is for you.

That said, after watching last Sunday’s performance at the Victory Gardens Theater, I was debating with myself as to whether to write a review of the production or simply an article about it. My hesitancy had to do with the fact that before the performance began, Producer/Director Dennis Začek, a veteran of Chicago theatre since the 1970s, stood up to announce that two characters would be played by “replacement actors.” Sure enough, two of the five actors read from scripts resembling Bibles throughout the show; this was something I had never seen before in a professional performance. We were encouraged to return at a future date when the show was perfected. So how could I fairly evaluate its quality on the basis of this unusual presentation?

I had the advantage of having previously seen a different production of “Waiting for Godot” years earlier, so I was already familiar with the story and its staging. Considering the play’s cerebral nature, pregnant pauses, and well-schemed humor, I knew that good but unrehearsed actors could perform well with this particular script. In fact, it was a joy to watch the two replacements memorize their lines on the fly. So after considerable thought, I concluded that watching a subsequent performance with scripts fully memorized would not make any difference as to how I would rate Začek’s production. With that prelude, it’s on to my review.

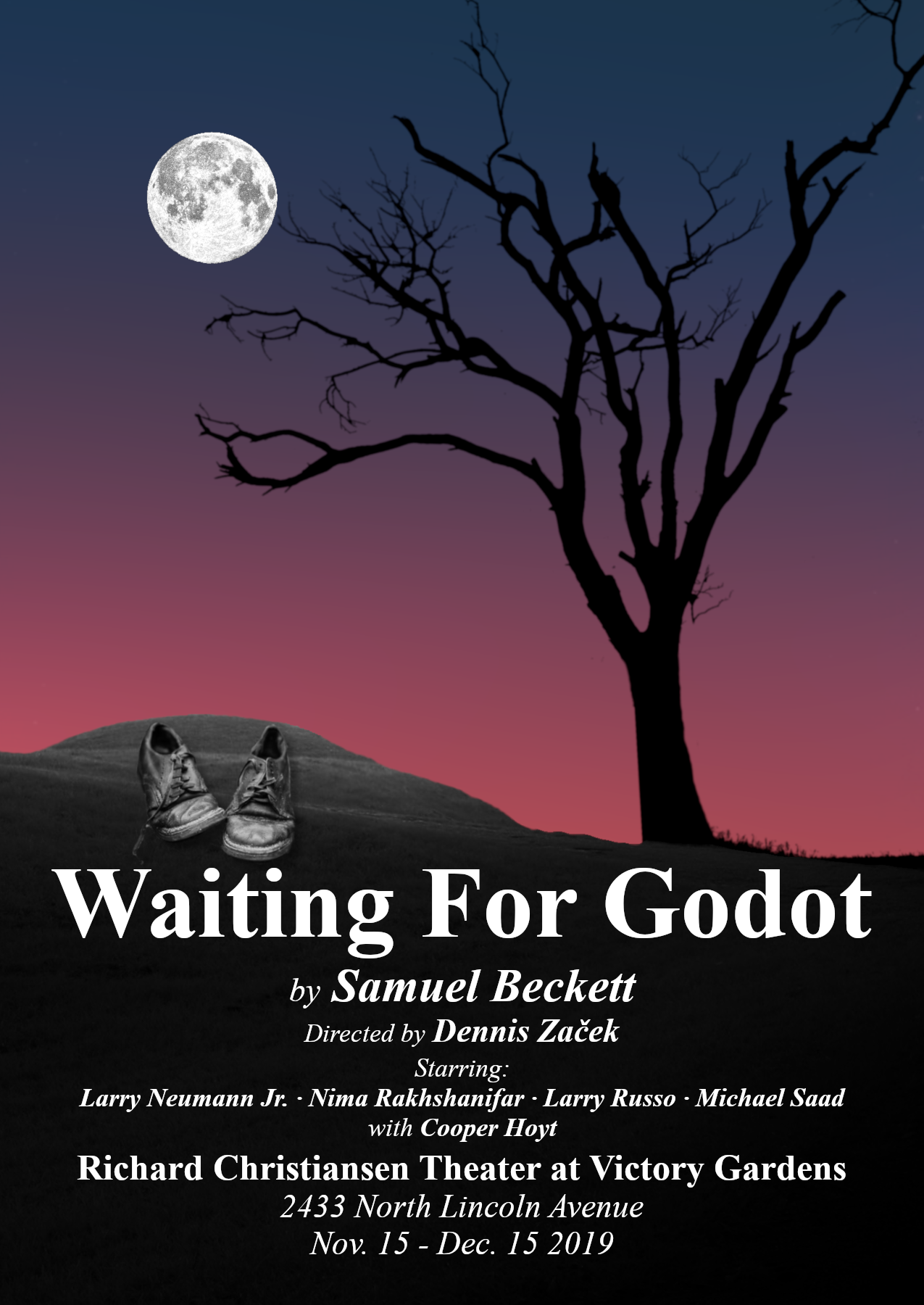

Over the years, patrons have retreated to the safety of the theatre to undertake spiritual quests to better understand themselves and their place within the universe. Such is the value of watching Samuel Beckett’s tragicomedy “Waiting for Godot.” Neatly lodged at a barebones physical and spiritual nexus—with minimalist set design—this intimate story can be considered a study of life’s meaning or lack thereof. It is a thoughtful reflection on religion and the human condition, and especially the role of human suffering.

Finished in 1949, “Waiting for Godot” was the first play that novelist Samuel Beckett had written. Though later considered his masterpiece, it nevertheless took three years for a theatre to accept it for production. It finally opened under the title “En attendant Godot” in 1953 at the Théâtre d’ Babylone, a small venue on Paris’s Left Bank. Since then “Godot” has been performed before audiences all around the world. Whereas some critics have deemed it incomprehensible if not also boring, other critics have lauded it as sheer magic: a witty take on existentialism and perhaps its opposite, realism, or taking things one day at a time, one moment at a time, with or without reflection—because that’s how things simply are. Beckett implies that there is no reason to ask what life is all about except that we, as human beings, have an innate desire to know. Regardless of our need to ask questions, understanding the meaning of life is all mere speculation anyway. It is no coincidence, then, that Beckett and the French existentialist Jean Paul Sartre were contemporaries.

Začek has done a fine job with his casting of Larry Neumann, Jr. as Didi and Mike Saad as Estragon. Wonderfully inspired with deeply dramatic facial expressions, the two actors play off each other beautifully and make a great team. They present themselves as the more contemplative version of Laurel and Hardy, or Abbott and Costello, who just happened to be working comedians during the time when Beckett was writing his script.

In both acts, Pozzo (Steve Pickering) arrives with his servant Lucky (a remarkable performance by Nima Rakhshanifar). At first Pozzo is taken for Godot, but the misidentification lasts but a moment. Pozzo abuses the hapless Lucky and  makes him suffer horribly, in theory for his own good. “It’s the only thing he understands,” says Pozzo, who is clearly not a moral person but eventually convinces Didi and Estragon that he truly is.

makes him suffer horribly, in theory for his own good. “It’s the only thing he understands,” says Pozzo, who is clearly not a moral person but eventually convinces Didi and Estragon that he truly is.

Godot in theory is supposed to save the two men—which is why they are waiting for him—at least, that’s what Didi maintains. The question is saving them from what? Is it from their misery of continuing to wait for him? Or from misery in general? Beckett shows us that whether or not we value or understand our existence on earth, its pain is always with us: physical, emotional, and spiritual. But Godot, the savior, is elusive—and never seems to show up. Who is he? the audience asks. And what has possessed Estragon and Didi to wait for him in the first place? That is the riddle. It is his absence that makes Godot notable. This is akin to a sequence in Sartre’s Being and Nothingness (1943) “Where is Pierre?” Pierre has been seen on prior occasions at a café but now is absent, like a child absent from school but whose name appears on the roster. But the absence of Godot is sight unseen and assumed. It is a different form of absence. As the men’s expectations to meet up with Godot are continually dashed, the audience is left wondering whether Godot has ever existed in the first place.

Fueled by confident and exemplary acting, the performance is a pleasant surprise: engrossing yet repetitive—much the way life is. Thinking, sleeping, forgetting, abusing, apologizing, and so on are routines that distract us from our existential misery. “Are we miserable?” asks Estragon of Didi at one point in the performance. Hence the play shows us that suffering is more a matter of degree than kind, since humans have been born to suffer in the first place—and those who seem to suffer more are those who constantly struggle with philosophical questions of “why?” and “why not?” How much of human suffering is the fault of God? Or perhaps the fault is with man and man’s inhumanity to man. Why has God created humans who not only perpetuate the existential condition of suffering but then add to it? Why does He not listen to His creation when we suffer so—and save us from our fate?

Costume design by Isaac Jay Pineda is nicely done. If suffering is good for the soul, then Didi and Estragon are aptly vagabonds and wear clothing from a previous era. Pozzo’s prosperous suit and Lucky’s unfortunate rags are designed equally well. Simple scenery and lighting by Patrick Kerwin make the audience wonder if the characters are in a real location or in some type of limbo. Or perhaps they are in a place within their inner selves where everybody is vulnerable.

Unlike being in the safety of the theatre, we are not handed a playbill at the beginning of our lives to know what the story is all about and what our particular role is supposed to be within the performance. We are not aware of who the production designer is and who is directing the action. “Waiting for Godot” postulates that in the end, we are free to imagine who or what is not there. As Estragon forgets more and more as the play proceeds and as Pozzo becomes blind and as the characters become more miserable, one lasting question remains: “Is this all a dream, or did it really happen?”

“Waiting for Godot” is playing at the Richard Christiansen Theater at Victory Gardens/Biograph Theater, 2433 N. Lincoln Avenue, Chicago, through December 15, 2019.

Performances are Wednesdays through Saturdays at 8:00 p.m., and Sundays at 4:00 p.m.

There will be no performance on Thursday, November 28 (Thanksgiving).

There is an added 4:00 p.m. matinee on Saturday, November 30.

Tickets are $20-$40. Discounts are available for students, seniors and groups.

For tickets and further information, visit victorygardens.org or call (773) 871-3000.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Waiting For Godot”.

More Stories

“Prayer for the French Republic” reviewed by Julia W. Rath ( and another by Paul Lisnek)

“Obliteration” reviewed by Mark Reinecke

” A Jukebox for the Algonquin”