*** “The Normal Heart” is Larry Kramer’s semi-autobiographical fictionalized play, based on the true story of his founding of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) in the early 1980s. In response to the growing HIV/AIDS epidemic, Ned Weeks (excellently portrayed by Peter Ferneding), seeks answers concerning this fatal disease infecting homosexual men in an environment when few people were willing to talk openly about gayness or acknowledge the huge number of deaths worldwide. Ned thus finds himself waging an uphill battle to raise awareness within the gay community about the disease. In so doing, he and his small but vocal group attempt to reach out to those in New York City government and politics to advocate for this marginalized population, so that eventually modern medicine might discover possible treatments for the disease—and ultimately a cure.

*** “The Normal Heart” is Larry Kramer’s semi-autobiographical fictionalized play, based on the true story of his founding of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) in the early 1980s. In response to the growing HIV/AIDS epidemic, Ned Weeks (excellently portrayed by Peter Ferneding), seeks answers concerning this fatal disease infecting homosexual men in an environment when few people were willing to talk openly about gayness or acknowledge the huge number of deaths worldwide. Ned thus finds himself waging an uphill battle to raise awareness within the gay community about the disease. In so doing, he and his small but vocal group attempt to reach out to those in New York City government and politics to advocate for this marginalized population, so that eventually modern medicine might discover possible treatments for the disease—and ultimately a cure.

While the origins of AIDS remained unknown and nobody knew how to treat it back then, one thing which was discovered rather early on was that it spread through unprotected sex and the exchange of bodily fluids: something which Doctor Emily Brookner (Tammy Rozofsky) states clearly at the onset of the show. Being a sympathetic practitioner of medicine to the gay community, she recommended sexual abstinence as a means of self-protection and for stopping the spread of the disease. The irony is that she suffers from polio and is wheelchair-bound because the Salk vaccine had not yet made its way into use until just months after she contracted the disease. So she is always optimistic that a successful medical treatment might be just around the corner.

We watch how the reality of AIDS affects both personal relationships, such as that between Ned and Felix Turner (Zachary Linnert), who are in a loving relationship with each other. We note the internal politics of GMHC and all of the controversies that the organization is involved with at a time when a significant number of gay men were not inclined to come out of the closet and admit their sexual orientation. The confrontations and discussions between the elected president Bruce Niles (Philip C. Matthews), Tommy Boatwright (Cameron Austin Brown), Mickey Marcus (Joshua Servantez), Craig (Caleb Crawford), and Ned are nicely spelled out; Ned and Mickey both use the analogy of the Holocaust as a parallel to the AIDS crisis: that nobody wants to acknowledge that people from a minority community are suffering and dying. Then we witness the conflict between GMHC and Hiram, a representative of Mayor Ed Koch’s administration (Gardy Gilbert) regarding the use (or non-use) of city funds to help combat the epidemic. Finally, there is Ben Weeks, an attorney and Ned’s (straight) brother (Christopher Meister), who loves his sibling but is offended by the man’s queer sexuality. Meister’s fine acting performance depicts Ben’s inner conflict very well.

While the script is good and meaningful, this production has lots of issues. For starters, the runway stage does not lend itself to the best presentation. Due to the large number of scene changes (which require that various props be constantly brought onto the stage and then removed), there were a few too many times when those of us in the first (and only) row felt that we had to pull our legs tightly into our chairs. Plus there were seven seats in the house where the audience members had major difficulties seeing the performance, and they constantly watched the actors’ backs. Even among the rest of us, the action was being obstructed far too many times by one character or another. There were also some “rogue lamps” on the ceiling whose light found their way into the eyes of some members of the audience. The director should have made sure ahead of time that every seat in the house was a good one.

Nine murals on the walls are quite artistic with photos of the gay community and many historical figures. There are clever sayings like “We’re here; we’re queer.” “Let me be perfectly queer.” “Hope will never be silent”, plus cards and envelopes so that theatregoers could write our own messages if we so wish. However, there should have been some wall space devoted to a more detailed history of the HIV/AIDS situation (from the 1980s and up into the current era), which could have put the presentation into better focus.

One of the most troubling issues has to do with the projection design. Contemporaneous documentary film and television, featuring Stonewall, newscasts about the spread of the “Gay Plague”, videotape from the Dick Cavett Show, and so forth, are used to place GMHC in historical and political context. These snippets are featured before the show, during intermission, and during scene changes whenever the set goes dark. While the idea behind using these projections is well-intentioned, they are not done well. On a technical level, I couldn’t figure out why the original aspect ratio of the film and TV footage could not have been preserved. But more importantly, while the footage may stir up memories among those of us who remember this time period, younger audience members may not recognize the people from forty years ago or understand the events taking place. So rather than enlightening us and providing us with some context for the play, the footage breaks things up a bit too much. Its inclusion in conjunction with all of the scene changes takes quite a bit of time, and this contributes to the show running unnecessarily long: for a total of three hours (including a 15-minute intermission). When I attended the performance on a weekday evening, it started fifteen minutes late and didn’t finish until 10:45 p.m.

The production gives us a glimpse of what it meant to be an activist for gay rights in New York City at a time when it was exceedingly difficult to raise awareness, not to mention funds, for GMHC, a fledgling organization devoted to combating HIV/AIDS. It demonstrates how frustrated and upset members of the gay community were with the inaction by those in positions of political power. We come to understand how psychologically overwhelming it can be to confront a major disease and, for that matter, any type of major crisis, especially one affecting a marginalized community. The show is at its best when we witness the characters’ emotions: about how they feel about loved ones and colleagues who have been lost or who are about to die. It is also great when we see the struggles among the different personalities about how best to advocate for the cause. The play resonated particularly well with my guest, who found it very relevant today and liked the performance somewhat more than I did. In contrast, I felt that there were a number of times when good acting could have substituted for so many soliloquys and that better staging could have easily shortened the downtime between scenes. In sum, while the material is excellent and the story compelling, the play is much too long to be as forceful as it needs to be.

Larry Kramer’s “The Normal Heart”, directed by Ted Hoerl, runs through September 29, 2024, at Redtwist Theatre, 1044 W. Bryn Mawr, in Chicago.

General admission tickets are $35, with discounts available for seniors, students and industry professionals.

Friday performances are “pay-what-you can.”

Friday performances are “pay-what-you can.”

Performance schedule:

Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays – 7:30 p.m.

Sundays – 3:30 p.m.

Special performances:

Understudy performance: Thursday, September 12th at 7:30 p.m.

Open-caption performances: Friday, September 6th at 7:30 p.m. and Friday, September 20th at 7:30 p.m.

Sensory performance: Sunday, September 8th, at 3:30 p.m.

For more information and to purchase tickets, please visit: https://www.redtwisttheatre.org/.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “The Normal Heart”.

More Stories

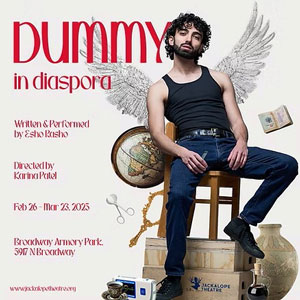

“Dummy in Diaspora”

“The Magic School Bus: Lost in the Solar System”

“February House” reviewed by Julia W. Rath