[rating=3]“The Lady from the Sea” is one of Henrik Ibsen’s least known plays; yet it expresses a very important theme: that we possess free will as individuals but generally find it easier to bow to societal customs and traditions that we actually might dislike or disagree with. Court Theatre’s production of this work contains unique directing by Shana Cooper, choreography by Erika Chong Shuch, and scenic design by Andrew Boyce. But it is not clear whether the additional layers of complexity and artistry tacked onto this production enhance or detract from the original story.

[rating=3]“The Lady from the Sea” is one of Henrik Ibsen’s least known plays; yet it expresses a very important theme: that we possess free will as individuals but generally find it easier to bow to societal customs and traditions that we actually might dislike or disagree with. Court Theatre’s production of this work contains unique directing by Shana Cooper, choreography by Erika Chong Shuch, and scenic design by Andrew Boyce. But it is not clear whether the additional layers of complexity and artistry tacked onto this production enhance or detract from the original story.

In 1888 in Ibsen’s Norway, married women were constrained in their social roles as wives and mothers. A so-called “bourgeois marriage” basically turned women into property, and women were not free to seek out their own interests or make decisions independent and separate from their husbands. Thus a good Norwegian wife would be praised for what she could do for others, rather than how true she might be to her own goals, ambitions, and needs. Ellida (Chaon Cross) is one such woman caught up in this traditional society. Ellida is—what could be called—a free spirit, who no longer wants to continue her conventional marriage. At an earlier stage in her life, she was content with making the accepted bargain with Dr. Wangel (Gregory Linington), a middle-aged widower. She agreed to take care of him and serve as a stepmother to his children, while he, in return, would care for her for the rest of her life. This means that she would be supported financially, live in pleasant surroundings, and have a respectable social position in society. Yet her changeable personality (resembling the ebbs and flows of the sea) makes her want to end the marital bargain with her husband and instead live a more independent life. More specifically, she wants to leave him to take up with an American sailor (Kelli Simpkins), a stranger and love interest from her distant past. And so Dr. Wangel, fearing for Ellida’s mental health, invites the highly educated Arnholm (Samuel Taylor) to his home in the hope that he can help his wife through this crisis. A former tutor to his daughter Bolette (Tanya Thai McBride), Arnholm is also Ellida’s former suitor.

The problem with the way that this production has been set up is that the audience questions whether we are dealing with the year 1888 or some later date. The main reason is this: In addition to Ellida’s pondering the nature of the human condition—and, more specifically, a woman’s place in society—this show is overlaid with issues concerning the exploration of straight versus gay and lesbian sexuality. Director Shana Cooper has introduced this interesting and worthwhile twist into this production, such that the American stranger (Ellida’s so-called “first” marriage partner) is not played by a man but by a woman (who is referred to as “he”). While adding this additional layer makes the story fresh, it changes the dynamics, but not in the way one may think. The shift in the sexual orientation of the lovers doesn’t alter the nature of love and longing in an existential sense—since having Ellida return to her first love would have been forbidden no matter whether this would have been a gay or a straight relationship. Either way, it would violate the sanctity of her marriage contract. Perhaps this is the point that the director is trying to make. But the exploration of sexuality per se pulls us away from the world of Ibsen’s writing. I can’t say whether this is a good or a bad thing: Perhaps I am the one caught up in history, but it’s no longer the tale exactly as he meant it.

This shift in emphasis becomes clear when overt comparisons are being made to conventional marital bargains as these relate to other characters, such as when Amholm discusses marriage with Bolette (who wants to be free to see the world) and when Lyngstrand (Will Mobley) discusses the nature of marriage with Hilda (Angela Morris)—and says that the only proper marriage that would satisfy a man and a woman would be for artists to marry each other. Then there is the character of Ballested (Dexter Zollicoffer), who is multidimensional in his interests and talents. And maybe that’s the secret to success in life: to find a purpose, whatever that may be, and not be overly concerned with existential questions for which there are no answers.

Then there is the issue of mental illness that this play raises. If there is any show that can point up how serious psychological issues may result from the strict adherence to women’s roles and the strong feeling of confinement, this is the one. When Ellida questions her role in the family and yearns to be free to be herself and make her own decisions, we oddly believe that she has literally gone off the deep end rather than sympathize with her plight. And that is not supposed to happen! The reason is that it has to do with the degree of her seeming mental illness. The analogy that Ellida is a mermaid is a nice one, for, in an instant, that describes how women are not being treated as fully human and are viewed by their male counterparts as a pretty attraction. But when it is unclear whether Ellida literally sees herself as being a mermaid, and that’s where the notion of “true” mental illness comes in. So it becomes logical that her husband would become very concerned when she suddenly responds to the “call of the wild” (or better “the ebb and flow of the sea”) and she becomes obsessed with the memory of the American sailor/stranger who once took hold of her emotions and romantic inclinations. Hence, the problem with this production is that it makes Ellida seem too mentally fragile, such that her desire for freedom seems much too irrational and erratic rather than firm and thought-out. She seems as if she needs help to sort out her life. Yet it is experimenting with new thoughts and feelings that finally makes Ellida truly human.

Boyce’s staging is interesting. We see sand and rocks and the characters walk barefoot. The water (the sea, if you will) is at the front of the stage and whenever a character goes into it or splashes themselves within it, the water is meant to represent truth. The sliding glass doors that the characters enter and exit from are reminiscent of living at a beach house, but the most exciting part is when the interior doubles as the ocean! Linda Roethke’s costume design features garments made from authentic patterns from late 19th and early 20th century; however, the signature costumes that Ellida wears—the green one in the first act and the red one in the second—are of more modern vintage, which again gives us timeline problems regarding this production. Lighting design by Paul Toben nicely enhances the mood throughout, especially in his use of various gobo disks to create light patterns in different scenes. Finally, Andre Pluess’s sound design is excellent.

“The Lady from the Sea”, adapted and translated by Richard Nelson, is the perfect show for National Women’s Month, as it describes what can happen when a society’s expectations for both men’s and women’s roles constrain all parties so much so that they no longer see the humanness of other people and instead see them as part of a commodity relationship. It makes a nod to American literature, which has a running theme of independence and rugged individualism. And yet there is another side to being human than just fulfilling individual wants and needs. To be free also means to accept responsibility for one’s actions and also to seek compromise with other people—who also want to be free! By wanting to drop her existing lifestyle and get rid of all her duties and obligations as a stepmother in order to be truly free has a certain arrogance about it. So that is probably why Ellida eventually does choose her routine life with Dr. Wangel over throwing her fate to the wind and starting over in a new/old fling. But now, that was her own choice to make! She makes the decision again to be married in a conventional way; however, this time, it is on her own terms!

“The Lady from the Sea” is playing through March 27, 2022, at The University of Chicago’s Court Theatre, 5535 S. Ellis Avenue, Chicago.

In-person and streaming tickets are both available by calling 773-753-4472.

In-person tickets start at $23.50. Go to: https://tickets.courttheatre.org/ for purchase.

Streaming tickets cost $35.00. Go to: https://overture.plus/patron/court-theatre for purchase.

For more information about this show, please turn to: https://www.courttheatre.org/season-tickets/2021-2022-season/the-lady-from-the-sea-2/.

For general information, visit https://www.CourtTheatre.org.

Note that COVID restrictions are still in effect. You will be asked for your vaccination card and ID, and you must wear a mask indoors.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at ” The Lady From the Sea”.

More Stories

“Mary Poppins : A Staged Concert” reviewed by Julia W. Rath

” I and You”

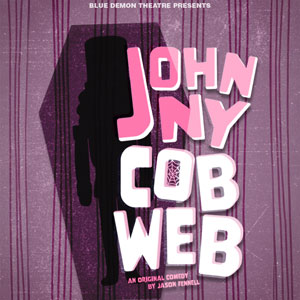

“Johnny Cobweb” reviewed by Mark Reinecke