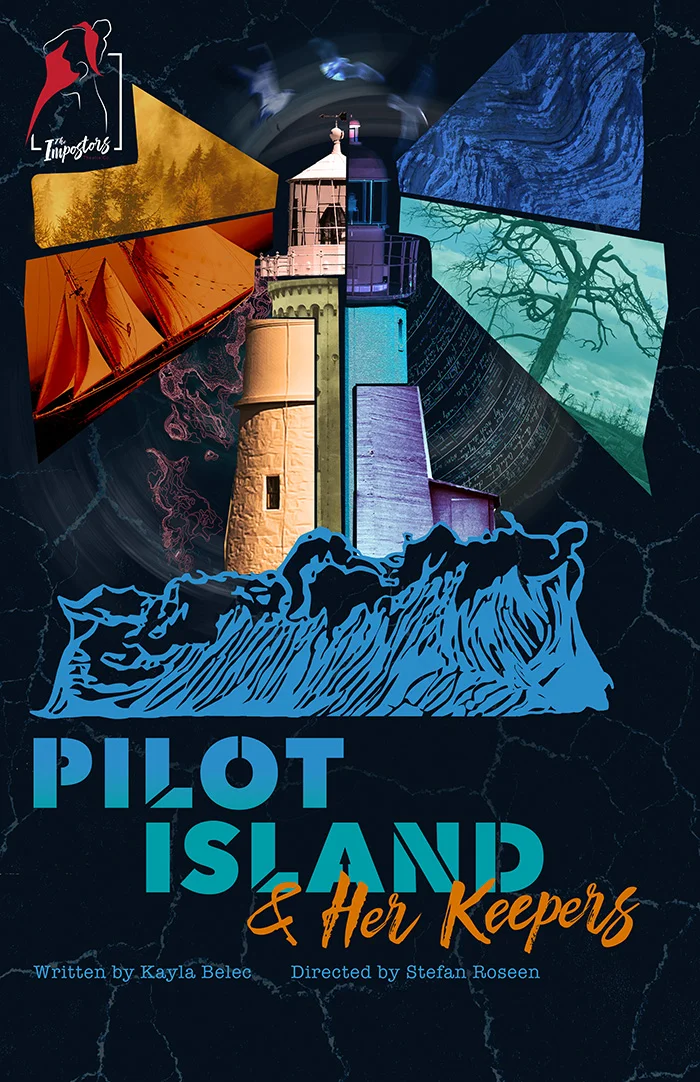

** Ever since their advent, lighthouses and foghorns have alerted seafaring vessels to navigation hazards and coastline dangers. In “Pilot Island & Her Keepers”, we learn something about the history of a lighthouse off the shores of Door County, Wisconsin, and about the people who manned it from 1876 to 1910. In this two-act performance, playwright Kayla Belec introduces us to the inhabitants of this desolate island and describes both the anxiety and loneliness inherent to being a lightkeeper—which is a twenty-four-hour job! Some portion of the show is devoted to eloquently composed statements, which describe the life and times of the characters and reflect on the profundity of life’s journey in general. But despite the fine acting, music, and dancing, not to mention the tremendously beautiful and meaningful uses of the English language, the play is too fragmented and hard to follow, and the genre is all over the place.

** Ever since their advent, lighthouses and foghorns have alerted seafaring vessels to navigation hazards and coastline dangers. In “Pilot Island & Her Keepers”, we learn something about the history of a lighthouse off the shores of Door County, Wisconsin, and about the people who manned it from 1876 to 1910. In this two-act performance, playwright Kayla Belec introduces us to the inhabitants of this desolate island and describes both the anxiety and loneliness inherent to being a lightkeeper—which is a twenty-four-hour job! Some portion of the show is devoted to eloquently composed statements, which describe the life and times of the characters and reflect on the profundity of life’s journey in general. But despite the fine acting, music, and dancing, not to mention the tremendously beautiful and meaningful uses of the English language, the play is too fragmented and hard to follow, and the genre is all over the place.

The production, directed by Stefan Roseen, opens with the audience becoming privy to hauntings by ghosts and spirits. This is a continual theme throughout. I’m not sure it goes anywhere… or maybe it does! The historical significance of Pilot Island is well-established shortly thereafter, when we learn about the dangers of sailing a craft on Lake Michigan, especially at the entrance to a once-treacherous corridor known as “Death’s Door.” This introduction to maritime history and geography is followed by a series of adventures that concern the island and the waters surrounding it. The larger story is mostly held together by narratives about what it means to look out for vessels in distress and when to sound the foghorn, together with tales about family life and friendship. The main characters include Captain Rohn (Ian Rigg), who retires from his job of lightkeeper in 1876 and hands the reigns over to Emmanuel Davidson (Riles Holiday) and his wife Christine (Keaton Stewart), who are originally from overseas. Later we meet their second assistant John Boyce (played by the actor with the fitting name of Andrew Shipman). Other characters include Mary Louise (Toria Olivier) and her husband Frank Pederson (Raul Alonso) and Gale (Zoë Bishop). There is also Martin Knudson who takes over as second assistant after John’s death and later runs the lighthouse himself.

What gets baffling, however, is that so much of this show is presented out of chronological order so that the moment you start to follow one thread, another suddenly pops up and the first one vanishes. With so many different sequences starting and stopping, combined with the constant movement of going forward and back in time, I constantly had to ask myself, “Did I miss something?” (This should not have come as a complete surprise, considering that the playbill lists seven narrators in the cast description.) Also somewhat confusing is when the same actor plays more than one role and there is no corresponding costume change (although they might change their accent).

More to the point, I found it troublesome when the script touches upon a number of genres at once. Psychological drama pervades the fascinatingly intimate scene between Emmanuel and John in the second act, where some elements of a possible murder mystery abound. In another tense segment, we witness the heart-stopping account of a ship about to be wrecked on the shores of Lake Michigan. In sharp contrast to both of these scenes, there is the merging of reality and myth in the account of Nellie the Cow, who needs to be tossed overboard to lighten a vessel’s load. Here we see a cow (a fine performance by Rigg) who talks, dances, and plays the accordion and accompanies the frolicky characters in their folk dancing to the lyrics of a sea shanty. (The beginning of the second act was a hoot, or should I say a moo?) While I loved the exuberant choreography by Anna Sciaccotta, the lively music by Dominick Alesia, and the fun nature of the cow, this joyfulness does not fit in with the realistic vibe of the performance. Having so many dancers gleefully participate in the hootenanny not only pulls the focus away from the loneliness theme but doesn’t fit the genre of realism, where the audience is being educated about the dangers at sea and especially about the residents’ isolation from the rest of humanity. Having said that, if the story is supposed to be an absurd or fantastical one, then there’s no reason for it to be so heavily grounded in history, complete with dates.

A multipurpose set design by Ethan Gasbarro works well for this show: Flooring that consists of wooden planks fastened together plus a faded brick background allows the audience to imagine the outside of a building as well as the deck of a sailing ship. Models of ships and schooners plus items such as ropes are a welcome part of the prop design by Jessica Miller and Jackie Bobbitt. The small model boat that is worn by one of the characters is particularly interesting. Emma Luke’s lighting design serves this production well. The light in the lighthouse is represented by a large lamp on the ceiling in red housing, and it is turned on at regular intervals. I especially liked how the characters towards the end each hold a lantern with a light shining through pinholes to represent the constellations. Ian R.Q. Slater’s dialect coaching could not have been done any better, as well as Erin Sheets intimacy design. But what I was most impressed with was the costume design by B Valek and Kayla Belec. The garments worn by all the (human) characters are great, as they are true to the time period. But my favorite was the ridiculously imaginative one for Nellie the cow.

There are lots of islands for boaters to navigate around between Wisconsin and Michigan, the largest being Washington Island, which can boast of some population as compared to Pilot Island with its now deserted and automated lighthouse since 1962. Today, however, it is for a Chicago audience to navigate this choppy tale that needs to be told in a more clear-cut manner. Basically, the script has to decide what genre it wants to be and stick with it. There needs to be some consistent organizing principle: for example, the reality that being on the island is much like being in prison, where time moves slowly and can slip away at a moment’s notice. Alternatively, the whole thing could be set to music where suddenly everyone breaks character and sings and dances about their situation. Or if the playwright wants the story to straddle more than one genre, then perhaps a dream sequence or some other irrational fantasy could be inserted into the plot, such that it becomes clear that we are being pulled away from normal reality. The script has potential, and there is room for improvement. That being said, the audience’s reaction seemed quite positive on the night I saw the show.

“Pilot Island & Her Keepers” played through November 23, 2024, at the Den Theatre, 1313 N. Milwaukee Avenue, in Chicago.

General admission tickets were $20

Performance schedule:

Thursdays through Saturdays – 7:30 p.m.

Sundays – 3:00 p.m.

For more information, visit https://theimpostorstheatre.com/

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Pilot Island & Her Keepers”.

More Stories

“The Magic School Bus: Lost in the Solar System”

“February House” reviewed by Julia W. Rath

” A Lie of The Mind”