[rating=5]Mary Bonnett’s heart-wrenching production “MIA: Where Have All the Young Girls Gone?” is a fresh and imaginative approach to the subject of teenage girls who have suddenly gone missing. The storyline is almost stream-of-consciousness, yet peppered throughout with anecdotes and statistics about women and girls who have vanished into thin air in today’s United States. Bonnett, using only two actors, personalizes the numbers with reference to a fifteen-year-old fictionalized teenager, aptly named Mia, abbreviated for “Missing in Action.”

[rating=5]Mary Bonnett’s heart-wrenching production “MIA: Where Have All the Young Girls Gone?” is a fresh and imaginative approach to the subject of teenage girls who have suddenly gone missing. The storyline is almost stream-of-consciousness, yet peppered throughout with anecdotes and statistics about women and girls who have vanished into thin air in today’s United States. Bonnett, using only two actors, personalizes the numbers with reference to a fifteen-year-old fictionalized teenager, aptly named Mia, abbreviated for “Missing in Action.”

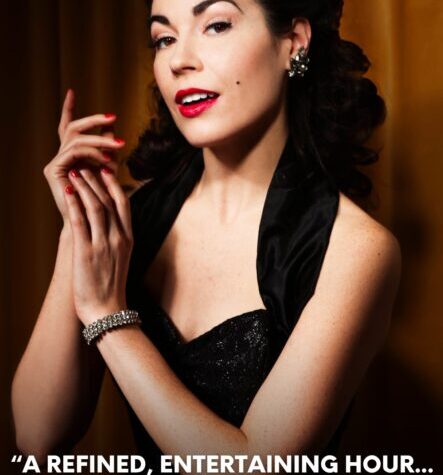

We watch the characters as they work to find the missing teen. Jamise Wright, in an incredible performance, plays both the part of Mia and her mother Mrs. Daltry with great conviction and fervor. Tristin Hall, as Essence, is superb as Wright’s foil and counterpart and plays a police officer, a social worker, and a trafficked woman among others. Mrs. Daltry combs Mia’s contacts (her friends, schoolmates, teacher, and principal) to develop possible leads. She engages the local police in her search and makes her family and her neighbors aware of her efforts. Despite her hard work, it is generally for naught. And then to what end? Many of these women are the target of some form of criminal activity, often sex trafficking or human trafficking or kidnapping. While missing individuals are common to all communities in the United States, a much higher proportion of black, Latina, and indigenous women are victims, relative to the overall population of women and girls.*

The raw emotions generated by both Wright and Hall are absolutely amazing, not to mention how well they turn on a dime when they portray one character and become the next. Throughout the show, we see expressions of grief and loss and disbelief on the part of the mother. We witness friends, relatives, and classmates of the missing person each responding differently to the frightful situation in ways that cannot be anticipated. Then there are necessary questions being asked by the authorities, such as, “How was she dressed when you last saw her?” There are also the unspoken opinions by acquaintances, such as “With the way she was dressed, was she asking for it?” As a contrast to these emotionally charged reactions, Hall dispassionately relates the statistics about the numbers of the lost and missing in Chicago and in the United States as a whole, aided by a computer monitor to the right and below the level of the stage. On the screen, we see photographs of actual women and girls whose whereabouts cannot be found, most of whom are teenagers. Sadly, we learn that the mainstream media has disproportionately focused on the plight of white women so that those from minority groups never seem to receive the attention that they most certainly deserve.

Bonnett’s word painting is marvelous! It is by means of monologues and the occasional dialogue that the audience can see just how brilliant her uses of language are in this show! Towards the beginning, Hall refers to how a person torn up by this unanticipated occurrence turns into a “shape-shifter.” In part, the use of this term could be thought of as playwright and director Bonnett’s self-critique concerning how she has chosen to structure the narrative. She knows from the onset that this work is intentionally comprised of slapdash splashes and insights, bound by her characters’ strong and palpable emotions and mannerisms. In fact, we witness how the timing, timbre, phrasing, and word choice varies from character to character, from the poetic to the brutally blunt. A smattering of quotations from known writers, such as Terry Pratchett, provide a framework for understanding the context for the moment when the missing and the mysterious merge into one. Just note that the way the story is told is not as graphic or gross as it otherwise could have been. We never see any physical abuse or scars—and never meet up with any abusers on stage, except by means of storytelling and by implication.

The production team, as a whole, has aimed for the minimalist. The play takes place on a mostly black box stage with just a few props: a chair or two, a ladder, and a cot. Christopher Persson’s music design could not have been any more perfect! He is an “experimental artist” who has created just the right mix of original songs and riffs that unobtrusively move the story along. Choreography by Melinda Wilson adds energy and lighter moments to the performance, making it not so grim. Lighting and sound design by Blake Cordell is seamless and effective.

The day I saw this world premiere production, Deputy Chief Dion Trotter, of the Special Victims Unit with the Cook County Sheriff’s Department, spoke to us afterwards about the work that his department is doing to find these missing persons. What was especially interesting was how well Deputy Chief Trotter picked up on the various nuances within this performance, which are thrown fast and furious at the audience. His commentary allowed all of us to see deeper meaning into events and experiences that might otherwise seem random, irrational, and possibly inexplicable. Among other things, it takes a long time to search for a person who has disappeared: much longer than what is being portrayed on typical TV shows. Despite the fact that loved ones typically try to keep the faith while looking for a lost soul, the outcome of their exploits is always uncertain. The end might be a good and positive one, but many of these individuals may never return home: either dead or alive. And if they are still alive, they may be physically, emotionally, or psychologically scarred, sometimes for life. However, the knowledge of the absolutely horrible thing may have happened to a loved one might give grieving parents, family, and friends some necessary closure.

This is not the first script that Bonnett has written which has focused on the plight of missing individuals and the struggles to find them. Seeking to protect and save women’s and children’s lives has been near and dear to the playwright’s heart for some time. As the artistic director of Her Story Theater, she is in a position to create such inspired works as this one so as to raise the consciousness of a Chicago audience. Therefore, it is no surprise that her passion in telling us this story is what makes it come alive. What the audience must constantly keep in mind is that each missing person’s case is a tragedy in its own right. As a result of watching this show, you too may want to embrace the mission of finding these disappeared young people and become equally devoted to this important cause.

“MIA: Where Have All the Young Girls Gone?” is playing through April 9, 2023, at the Greenhouse Theater Center, 2257 N. Lincoln Ave., Chicago.

Tickets: $20.00

Tickets: $20.00

Students: $10.00

Performance Schedule:

Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at 8:00 p.m.

Sundays at 2:00 p.m.

To purchase tickets, go to https://ci.ovationtix.com/36644/production/1149792 or visit the Greenhouse Theater website: www.greenhousetheater.org or phone 773-404-7336.

For further information about this show and to inquire about group rates for tickets, visit www.HerStoryTheater.org or call 312-835-1410.

To learn more about the Greenhouse Theater and its other offerings, go to https://www.greenhousetheater.org/.

COVID-19 protocols at the Greenhouse Theater are always subject to change. Masks are strongly encouraged at this time. Email boxoffice@greenhousetheater.org or phone 773-404-7336 for the latest updates.

*One such statistic, for example, is this: “In 2020, 268,884 women were reported missing, according to the National Crime Information Center, with nearly 100,000 of those being black women and girls.”

To see what others are saying, visit , go to Review Round-Up and click at “MIA:Where Have All the Young Girls Gone?”.

More Stories

“Cats”

“Two Sisters and a Piano”

“Hamilton” Reviewed by Paul Lisnek “Curtain Call Chicago”