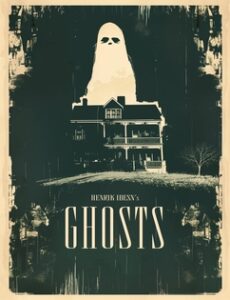

***** Henrik Ibsen’s “Ghosts” tells a tale about family secrets kept for decades and the emotional toll that this has taken. Now a one-act production smartly directed by Jimmy Piraino and adapted by the Gwydion Theatre ensemble, the play is fresh and exciting and features updated prose. This story from 1881 Norway points up the gap between the moral way of life advocated by the Protestant Church versus the way that most middle-class people actually lived their lives: behind a veil of convention, respectability, and domesticity. The original play would have been scandalous and norm-shattering back in the day, because it brings up all sorts of uncomfortable truths, such as cheating husbands, bad marriages and divorces, and premarital and extramarital relations. It introduces ideas about assisted suicide, incest, and other taboo topics, such as a frank discussion about syphilis, which, at the time was considered a likely punishment from God for lustiness and a licentious lifestyle: roughly fifty years before the sexual transmission of disease was fully known or understood scientifically.

***** Henrik Ibsen’s “Ghosts” tells a tale about family secrets kept for decades and the emotional toll that this has taken. Now a one-act production smartly directed by Jimmy Piraino and adapted by the Gwydion Theatre ensemble, the play is fresh and exciting and features updated prose. This story from 1881 Norway points up the gap between the moral way of life advocated by the Protestant Church versus the way that most middle-class people actually lived their lives: behind a veil of convention, respectability, and domesticity. The original play would have been scandalous and norm-shattering back in the day, because it brings up all sorts of uncomfortable truths, such as cheating husbands, bad marriages and divorces, and premarital and extramarital relations. It introduces ideas about assisted suicide, incest, and other taboo topics, such as a frank discussion about syphilis, which, at the time was considered a likely punishment from God for lustiness and a licentious lifestyle: roughly fifty years before the sexual transmission of disease was fully known or understood scientifically.

The play begins when we see Regina Engstrand (Ellie Thomson) straightening things up the Alvings’ house and dusting all the living room and dining room furniture. From all appearances, the Alvings are staunchly upper-middle class. Regina has been taken in as a maidservant, considering that her father Jacob Engstrand (played to perfection by Stephen Fedo) cannot fully provide for her needs. Towards the start of the show, Engstrand visits Regina and explains to her that he no longer wants to be employed at the local orphanage, run by Pastor Manders (Phil Aman). Rather than teaching woodworking, he would prefer to open a (disreputable) home for retired sailors, and he asks Regina to join him. She implies that her morals do not allow her to assume this sort of role, and she has no use for a father who drinks heavily and advocates prostitution. Rather, she’d prefer to remain in the employ of Mrs. Helene Alving (Jeanne Scurek), a widow whose husband died ten years prior. In fact, we learn that the orphanage was previously established by Mrs. Alving in memory of her late husband, and apparently Pastor Manders was to stop by to discuss insurance matters and other concerns related to its management.

In the course of their visit, Pastor Manders brings up all sorts of other issues with Mrs. Alving, largely having to do with matters of morality and decency. Particularly, he thinks that Regina should leave the Alvings’ home and become of help to her elderly father by living with him. But Mrs. Alving is not too happy about that possible arrangement and breaks her silence when it comes to certain family secrets. That is when the pastor learns about how an outwardly respectable family has deviated from the lifestyle that he believes Scripture must dictate. Among other things, he finds out that Mrs. Alving hid public knowledge of the affair that her late husband once had with their maid Johanna. At the same time, Mrs. Alving’s son Oswald (Tommy Thams) has apparently “inherited” his father’s tendencies for alcohol abuse and libertinism. Having recently returned from his stint in Paris, Oswald suffers from syphilis (which was fatal back in the day). Plus he has a yearning for some type of relationship with Regina, who he feels would take better care of him (and his illness) as compared to his mother.

While the audience may wonder about the degree to which Oswald took after his father, the more important question is this one: “To what extent have all the characters’ lives been touched by the late Mr. Alving and his drunken, debauched, depraved, and disgusting self?” Evidently, memories of the man constantly hang around the house, elevating him to an almost ghostlike presence that haunts everybody in the same way that a large portrait of him (with a blanked-out face) haunts all who enter the house. Macabre in its appearance, the painting is a credit to Maddy Asma’s artwork and finds its way to the playbill’s cover.

Set and prop design by artistic director Grayson Kennedy is good and appropriate for this production. It’s simple enough to serve as a backdrop for all of the action, and the vintage couch with wood trim is especially beautiful and time-specific. Piriano’s directing is splendid when Regina throws up a muslin sheet (previously used to cover some furniture) and attaches it to the back of the archway that separates the front room and the back. Later, through the lens of lighting designer Sam Besser, this part of the stage is used as a screen for projecting backlit images of real or imagined ghosts as well as suggesting the fire that consumes the orphanage.

I loved all the authentic costumes (created by the unnamed costume designer). Regina’s black and white maidservant outfit tells us everything we need to know about her and her place in society. Engstrand, her elderly father, is dressed as a poor man, complete with a cane, which he constantly raps to draw attention to himself. Helene Alving is the only one wearing a colorful garment in keeping with her social status. And of course, the pastor is dressed in his traditional clerical garb. But what I liked best was when Oswald enters the stage wearing contemporary black and white checked drawstring pajamas! This was such a wonderful touch! Rather than having the audience laugh at the men’s sleepwear fashion of the late 19th century, we are immediately confronted with this anachronistic garment, which focuses our attention on the man’s unconventionality, and it silently makes the point that his morality is probably closer to those of young people in the present-day. Also in an instant, we know that something is very wrong, for why else would he be wearing pajamas when everybody else is fully dressed? Similarly, the introduction of the gun is a significant improvement on the original script that works well for a modern audience. It is a change that brings back the tension and drama from years past.

After watching the performance, I started to think more about the story’s very beginning: where Regina lifts the covers off all the furniture and dusts the room for nearly eighteen minutes, so as to make the house presentable for company. Perhaps this extended introduction is meant to symbolize how the furniture is often treated with more respect and care than family members. Or perhaps it foreshadows the airing of the Alving family’s secrets in public. In any event, the revealing of an embarrassing, if not traumatic, family history knows no time period, and I think it’s fair to say that memories of those who are no longer with us often cast a bright light or a dark shadow throughout our entire lives. Furthermore, with today’s growing trend to conduct genealogical research on one’s own family, the discovery of unpleasant truths, illicit relationships, and unflattering states of affairs has become all the more commonplace—with our distance from these actual events making their knowledge not only more accepted but sought-after. Thus, it is our modern perspective that makes “Ghosts” just as relevant today as it might have been when the show first opened over 140 years ago.

“Ghosts” by Henrik Ibsen is playing through March 9, 2025, at the Greenhouse Theater Center, 2257 N. Lincoln Avenue, in Chicago, inside their “Up Studio” space.

General Admission Tickets: $32 (includes a $2 facility fee) plus a $4 convenience fee

Performance schedule:

Performance schedule:

Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays – 7:30 p.m.

Sundays – 3:30 p.m.

For more information or to purchase tickets, see: https://ci.ovationtix.com/36644/production/1200341 or email the box office at boxoffice@greenhousetheater.org.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Ghosts”.

More Stories

“The Firebugs” reviewed by Julia W. Rath

“The Book of Grace” Al Bresloff with another from Paul LIsnek

“The Last Five Years” MILWAUKEE