*** “Fidelio” is the only opera Ludwig van Beethoven composed music for, and for that reason alone, it would have a place in history. It’s also an outstanding example of Beethoven’s ability to make the heart soar through the right interpreters and was an important landmark for female protagonists onstage when its climax surprised and thrilled audiences in 1805. And with a libretto full of declarations of hope for liberty and love remaining steadfast against opposition, its themes remain evergreen. Perhaps too evergreen; its villain is so ridiculous that people advocating for absolutely any ideology can boo him, and the resolution so jarringly arbitrary it was parodied in The Threepenny Opera. Still, the performers in the new-to-Chicago production at the Lyric Opera, directed by Mathew Ozawa and conducted by Lyric Music Director Enrique Mazzola, play it with absolute earnestness, bringing out the full emotional power in Beethoven’s music.

*** “Fidelio” is the only opera Ludwig van Beethoven composed music for, and for that reason alone, it would have a place in history. It’s also an outstanding example of Beethoven’s ability to make the heart soar through the right interpreters and was an important landmark for female protagonists onstage when its climax surprised and thrilled audiences in 1805. And with a libretto full of declarations of hope for liberty and love remaining steadfast against opposition, its themes remain evergreen. Perhaps too evergreen; its villain is so ridiculous that people advocating for absolutely any ideology can boo him, and the resolution so jarringly arbitrary it was parodied in The Threepenny Opera. Still, the performers in the new-to-Chicago production at the Lyric Opera, directed by Mathew Ozawa and conducted by Lyric Music Director Enrique Mazzola, play it with absolute earnestness, bringing out the full emotional power in Beethoven’s music.

Leonore (soprano Elza van den Heever) has infiltrated a prison in the guise of a male guard named Fidelio in hope of finding her husband, Florestan (tenor Russell Thomas). She’s made some progress; Marzelline (soprano Sydney Mancasola), the daughter of the chief jailor, Rocco (bass Dimitry Ivashchenko), has fallen in love with her alter ego, and Rocco is fond of her, too. After encouraging them to get married and gifting them a large sum of money, Rocco reveals to his new best friend that there is an inmate the governor of the prison, Pizarro (baritone Brian Mulligan) wants kept off the records. But just then, Pizarro gets a tip-off that the prison is going to be inspected, and he orders Rocco to dispose of the prisoner before he is found.

It turns out that Pizarro had Florestan extrajudicially kidnapped and has been keeping him tied to a chair in a storage room for two years. (It’s unclear how Leonore became aware he was alive or suspected he was in the prison.) This is typical of Pizarro, who, in Matthew Ozawa’s production, frequently points his gun at the guards when he isn’t smacking them and lunges and snarls every time he passes by the pen where child prisoners are held. The libretto also has him throw a fit because Rocco allowed the prisoners into the yard and gives him an aria about how he’s going to devise the cruelest death possible for Florestan, although what he comes up with is a literal coup de grâce. The narrative is also very clear that Pizarro’s personal foibles are the sole source of all the injustice in this system; his minions shake their heads sadly and tremble as he rages, Pizarro takes for granted that the discovery of any abuse in the prison will result in his firing, and his dismissal carries an assumption of everybody being released, implying none of the people in this prison were being held legally at all.

The early nineteenth century wasn’t a time when operas were known for their plots, so it’s reasonable to make some allowances for the sake of Fidelio’s music. The Lyric chorus’s rendition of the famous “O welche Lust,” as well as van den Heever’s “Komm, Hoffnung” and Thomas’s “Gott! Welch Dunkel hier!” are beautiful and meditative, and van den Heever plays the comic first half of the opera with just as much sincerity as the dramatic second. Alexander V. Nichols’s set and projection design are also quite clever. Whereas Beethoven’s music is too otherworldly to fit comfortably into a realistic story, Nichols’s office, stacks of holding pens, and cluttered basement are brutally institutional, uncomfortable, and intentionally ugly. Since Fidelio has been popular for over two hundred years, clearly not everybody shares this reviewer’s problem with its apparent attempt to say something meaningful about oppression by scapegoating a single Looney Tunes villain for everything bad in the world. Perhaps The Threepenny Opera was pushing against the meta-narrative surrounding Fidelio as much as the work itself, which might not be fair to it. Beethoven’s hearing loss prevented him from ever working in such a collaborative medium again, but singing actors can still use his music to channel a sublime mood and strike an evocative pose.

Fidelio will continue at the Lyric Opera House, 20 N Upper Wacker Drive, Chicago, thru October 10, with the following showtimes:

October 5: 7:30 pm

October 10: 7:00 pm

Running time is two hours and thirty minutes with one intermission. There is also a thirty-minute preview talk an hour before the show.

Performances are in German with supertitles.

Ticket prices start at $52. The Lyric offers parking deals with Poetry Garage at 201 W Madison St. if inquired about in advance. To order, visit or call 321-827-5600.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click “Fidelio.”

More Stories

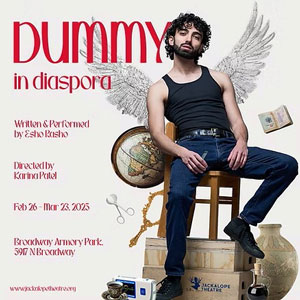

“Dummy in Diaspora”

“The Magic School Bus: Lost in the Solar System”

“February House” reviewed by Julia W. Rath