rating=3] There’s a moment in the Lyric Opera’s production of Don Carlos when the titular floppy-haired prince interrupts a mass execution of heretics to hand-deliver his father a stack of petitions from Flemish Protestants, and his mouth falls open in shame and astonishment when the king throws his hard work on the ground and calls him a screw-up in front of the whole Spanish Inquisition. In this telling, you could even call it the key to his character. Giuseppe Verdi’s music for his own version of French Grand Opera is rich and dynamic, equally evocative of massive crowds and constricting interiors. Don Carlos has maintained a respected place in the repertoire for a century and a half, although it was never performed as often as shorter Verdi works that have definitive versions and hasn’t appeared at the Lyric since 1996, and only in Italian. And if the Lyric’s current French-language production, originally directed by Sir David McVicar with revival direction by Axel Weidauer, doesn’t always create complex visuals or convincing psychology, it does feature outstanding musical talent and a lot of interesting moments in a very strange script.

rating=3] There’s a moment in the Lyric Opera’s production of Don Carlos when the titular floppy-haired prince interrupts a mass execution of heretics to hand-deliver his father a stack of petitions from Flemish Protestants, and his mouth falls open in shame and astonishment when the king throws his hard work on the ground and calls him a screw-up in front of the whole Spanish Inquisition. In this telling, you could even call it the key to his character. Giuseppe Verdi’s music for his own version of French Grand Opera is rich and dynamic, equally evocative of massive crowds and constricting interiors. Don Carlos has maintained a respected place in the repertoire for a century and a half, although it was never performed as often as shorter Verdi works that have definitive versions and hasn’t appeared at the Lyric since 1996, and only in Italian. And if the Lyric’s current French-language production, originally directed by Sir David McVicar with revival direction by Axel Weidauer, doesn’t always create complex visuals or convincing psychology, it does feature outstanding musical talent and a lot of interesting moments in a very strange script.

Suppose that you are a teenaged princess who is known for being smart instead of pretty, with feckless, stupid siblings and a terrifying, controlling mother. To bring about peace between the world’s warring superpowers, you are engaged to marry a dark and brooding prince with daddy issues, a bad reputation, and a jaw that can cut steel. And then, at the last minute, the prince’s gross, middle-aged, ultra-Catholic father changes his mind and takes you for himself. You are the French princess Elisabeth, here played by soprano Rachel Willis-Sørenson, whose tragedy is not that she and Carlos were doomed lovers, but that they denied themselves love and lost everything anyway. The court intrigue revolves around France’s separate peace with Spain being a disaster for the anti-Spanish Flemish rebels, whose sympathizer in the palace, Rodrigue (baritone Igor Golovatenko), haplessly attempts to exploit the royal love triangle to get them a better deal. It goes badly for everybody, but especially him and Carlos.

Carlos is played by the powerhouse tenor Joshua Guerrero. His version of the character is emo and apparently a bit dim, but very earnest. In contrast, King Philippe, played by bass Dmitri Belosselskiy, is pessimistic, isolated, and endures mounting frustration over the opera’s four-hour running time due to his son’s willful incomprehension of what it takes to build the sort of legacy that results in still having a country named after you in five hundred years. His aria “Elle ne m’aime pas” at the start of the fourth act about his realization that he has made two young people he cares for miserable, is a compelling depiction of downward spiraling, beautifully delivered, as is Willis-Sørenson’s rendition of “Toi qui sus le néant,” in which Elisabeth seems to contemplate suicide out of hope that it will stop Philippe and Carlos’s fighting. Don Carlos also contains some of the mature Verdi’s best-known duets, including Guerrero and Golovatenko’s sweet tenor-baritone friendship ode “Dieu, tu semas dans nos âmes,” and one of the most famous duets between two basses, the confrontation between Philippe and the Grand Inquisitor, played by the imposing Soloman Howard. The play by Friedrich Schiller that Verdi was adapting was generally much more interior and contemplative than the epic Verdi tried to balloon it into, and this reviewer found McVicar’s concept to be much more favorable to the scenes of moody monologues and dialogue that didn’t require much action.

At several points in the play characters consider removing themselves from the situation in hope that things will settle down with them gone, and this is apparently what Rodrigue is hoping for by convincing Carlos to take command of the conflict in the Low Countries. Alas, they cannot leave, and original set designer Robert Jones represents the play’s entire world as the stark, dungeon-like tomb of the late emperor, Philippe’s father. Personally, I can’t say this restrained concept worked that well for me; even the mob at the auto-da-fé comes across as regally smug instead of bloodthirsty. But Don Carlos is also a difficult thing to find a concept for. It’s a Risorigmento anti-Habsburg exultation of liberty and rebellion that is written so that Napoleon III could feel comfortable attending the premiere at a time when he needed the Habsburgs to balance Prussia. It’s not clear to a modern audience that what the Flemish were fighting for was what we would call “liberty,” and even if you pretend that the real Prince Carlos was an opponent of the Inquisition and Spanish imperialism, it’s impossible to pretend that he succeeded at preventing them. Indeed, his final scenes in the opera are a self-loathing lament that he has thrown his life away for nothing, though Verdi made it ambiguous and open-ended what actually happens to him and this version of the script raised the possibility of him starting life over with a new identity. (However, downplaying Carlos’s and Princess Eboli’s historical distinctive disabilities for reasons of plot and sex appeal, while giving a disability to the fictional Grand Inquisitor explicitly to represent his immoral character, wasn’t the coolest thing Verdi ever did.) Frankly, I thought Golovatenko’s Rodrigue came across like he was manipulating a vulnerable person, and I’m not sure that was the original or revival director’s intent.

conflict in the Low Countries. Alas, they cannot leave, and original set designer Robert Jones represents the play’s entire world as the stark, dungeon-like tomb of the late emperor, Philippe’s father. Personally, I can’t say this restrained concept worked that well for me; even the mob at the auto-da-fé comes across as regally smug instead of bloodthirsty. But Don Carlos is also a difficult thing to find a concept for. It’s a Risorigmento anti-Habsburg exultation of liberty and rebellion that is written so that Napoleon III could feel comfortable attending the premiere at a time when he needed the Habsburgs to balance Prussia. It’s not clear to a modern audience that what the Flemish were fighting for was what we would call “liberty,” and even if you pretend that the real Prince Carlos was an opponent of the Inquisition and Spanish imperialism, it’s impossible to pretend that he succeeded at preventing them. Indeed, his final scenes in the opera are a self-loathing lament that he has thrown his life away for nothing, though Verdi made it ambiguous and open-ended what actually happens to him and this version of the script raised the possibility of him starting life over with a new identity. (However, downplaying Carlos’s and Princess Eboli’s historical distinctive disabilities for reasons of plot and sex appeal, while giving a disability to the fictional Grand Inquisitor explicitly to represent his immoral character, wasn’t the coolest thing Verdi ever did.) Frankly, I thought Golovatenko’s Rodrigue came across like he was manipulating a vulnerable person, and I’m not sure that was the original or revival director’s intent.

But with those reservations stated, Don Carlos is magnificent music, and the skilled conducting of Enrique Mazzola and the singers in the cast do it justice. Personally, I find the mess of the never-fully-settled-upon script to be a glorious one that produces a lot of good character dynamics and interesting ideas amid music that never fails at conveying an emotion, even if not all the other elements are as strong. Clémentine Margaine, as the long-suffering Princess Eboli, deserves particular acclaim for her alluring stage presence. Someday, somebody might write a dramatization based on a more authentic version of the story of Felipe II and Prince Carlos. (Contrary to what the opera implies, they barely had an eighteen-year age gap.) But the historical oddities of Verdi’s script are themselves fascinating, and productions of the French version are still rare enough for this to be an exciting opportunity.

Don Carlos will continue at the Lyric Opera House, 20 N Upper Wacker Drive, Chicago, thru November 25, with the following showtimes:

Don Carlos will continue at the Lyric Opera House, 20 N Upper Wacker Drive, Chicago, thru November 25, with the following showtimes:

November 17: 2:00 pm

November 20: 2:00 pm

November 25: 7:00 pm

Running time is three hours and fifty minutes with one intermission.

Performances are in French with English supertitles. Streams are available to ticket purchasers.

The Lyric offers parking deals with Poetry Garage at 201 W Madison St. if inquired about in advance. Tickets start at $50; to order, visit LyricOpera.org or call 321-827-5600.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click “Don Carlos.”

More Stories

“The Last Five Years” MILWAUKEE

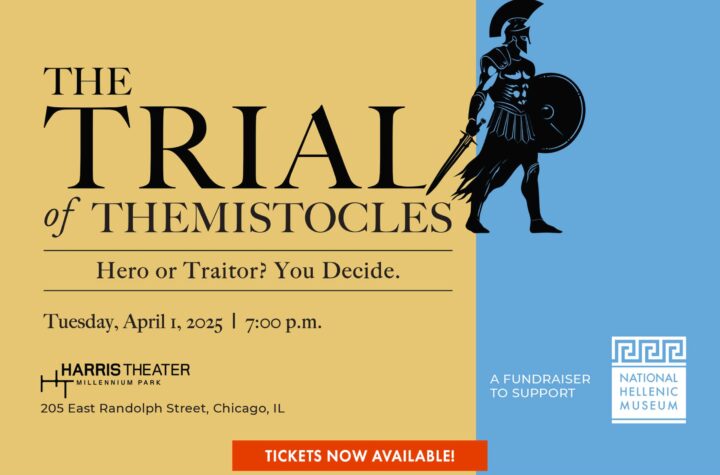

“The Trial of Themistocles” reviewed by Julia W. Rath

“Titanique”