Highly Recommended ***** The story of Dead Man Walking is narrowly focused. It takes place over a few weeks and mostly in the Louisiana State Penitentiary (a.k.a. Angola) or in a nun’s living quarters and the road between. But it is so tightly wound emotionally that its conclusion requires the full powers of one of the world’s great opera houses to set in motion. Adapted by composer Jack Heggie and librettist Terrence McNally from the memoirs of Sister Helen Prejean, it depicts an execution and Prejean’s spiritual ministering to a condemned man. Dissonant and imposing, few compositions could be grimmer, but it is also tender enough to fascinate and elicit the audience’s vulnerability.

Highly Recommended ***** The story of Dead Man Walking is narrowly focused. It takes place over a few weeks and mostly in the Louisiana State Penitentiary (a.k.a. Angola) or in a nun’s living quarters and the road between. But it is so tightly wound emotionally that its conclusion requires the full powers of one of the world’s great opera houses to set in motion. Adapted by composer Jack Heggie and librettist Terrence McNally from the memoirs of Sister Helen Prejean, it depicts an execution and Prejean’s spiritual ministering to a condemned man. Dissonant and imposing, few compositions could be grimmer, but it is also tender enough to fascinate and elicit the audience’s vulnerability.

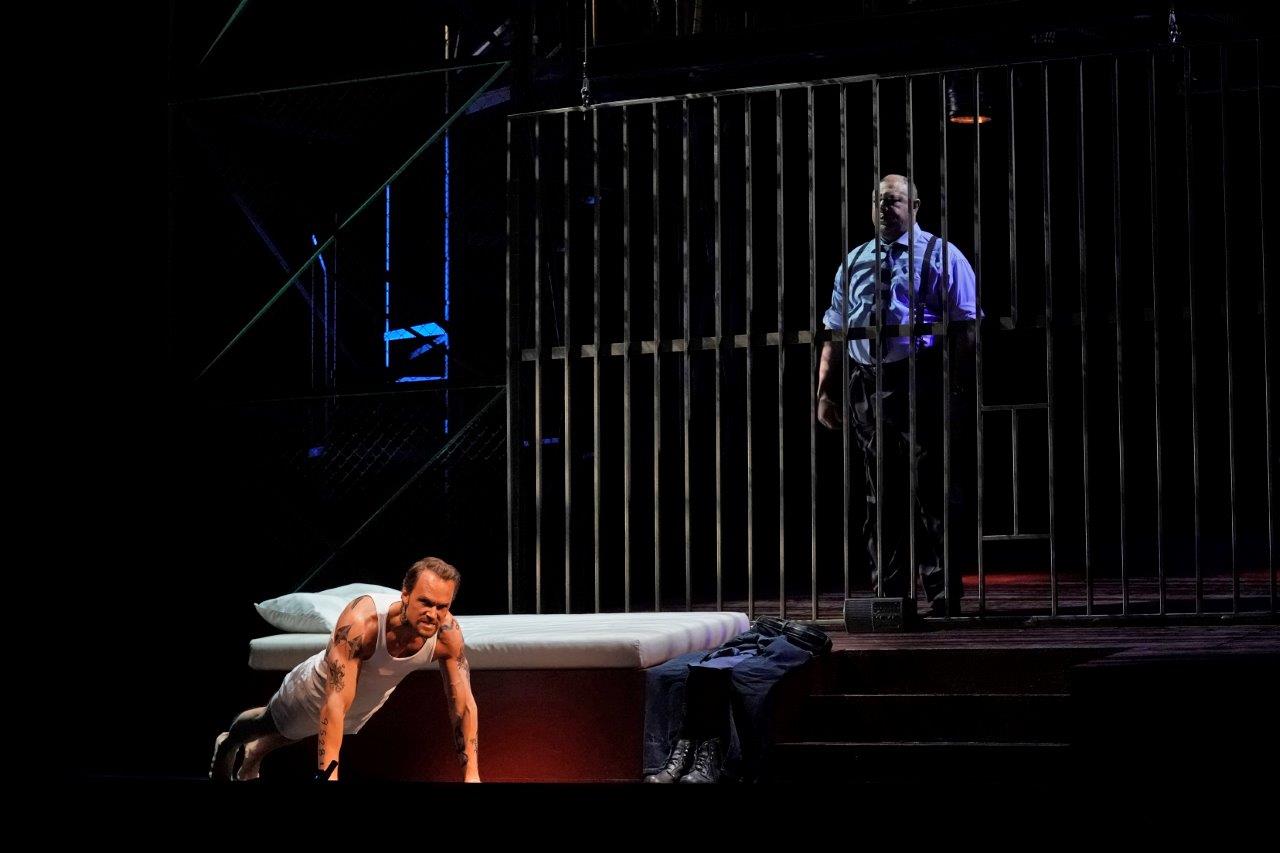

We know that this will be unusual fare for an opera from something incredibly simple in the opening scene: realistic sound effects. A young couple is frolicking nude while listening to their car radio on a muggy summer night. They cannot hear the sinister men creeping up on them from the shadows until it is too late. This is the rape and double-murder Joseph de Rocher is sentenced to death for committing with one of his brothers, and the frank brutality with which it is depicted is shocking. Sister Helen (soprano Patricia Racette) does not understand the crime and probably never will. But she has taken Joseph as her pen pal through a prison ministry program, and when he says he wants to meet her in person, she quickly agrees.

Sister Helen knows this choice seems reckless, but she declares in a soliloquy that becoming a nun in the first place was a wild risk and the best thing she ever did. The prison is awful; though expected, nothing could really prepare her for it, and the warden (Gordon Hawkins), has more disconcerting news. Joseph’s execution is imminent and he is auditioning spiritual advisors who will be present with him while he dies if his last appeal is denied. Moreover, he continues to implausibly and inconsistently deny his guilt, making him particularly frustrating for ministers of his claimed Catholic faith. Sister Helen meets him nonetheless, and although their introduction isn’t particularly encouraging, Joseph does express concern for his mother and innocent youngest brothers, and Sister Helen agrees to assist them during the appeals process. After that, she pretty much feels obliged to see it through.

Racette’s Sister Helen isn’t naïve, exactly. She’s a mature woman who understands her religion and came from a hardscrabble background not far from Angola. But she apparently started her prison counseling with the hardest case, and ordinarily being a children’s teacher, she tends to slip into that tone with other adults. When the parents of the victims accuse her of making them seem like the bad guys, she can only stammer a pathetic “I’m sorry.” Joseph (bass-baritone Ryan McKinny) speaks in a Southern croon conducive to irony and, while younger than Sister Helen and uneducated, is by no means unintelligent. But he is very cynical. Mezzo-soprano Susan Graham originated the role of Sister Helen nineteen years ago in San Francisco, but in this production, she plays Joseph’s mother. Exhausted, bewildered, and terrified, she does not even get the community sympathy afforded to the victim’s parents and gives voice to the criminal justice system’s unintended, secondary victims. Tellingly, the position of the microphone at the appeals hearing forces her to bend her head down while begging for her son’s life. Each of these performers is rightly praised for their singing chops, but these roles are also among the most challenging in opera from an acting standpoint. In that regard, they’re utterly transfixing and entirely believable, responsible for as much of the passion onstage as the music itself.

Production director Leonard Foglia’s vision is a harsh one. Projection designer Elaine J. McCarthy’s selection of photographs from Louisiana’s endless stretches of highway overlay the cruel metal of Michael McGarty’s set. Terrence McNally, whose plays frequently grace Chicago stages but who has never had an opera at the Lyric before, wrote a refreshingly straightforward libretto. Jake Heggie, whose challenging score is conducted by the sure hand of Nicole Paiement, wanted a sound that would significantly differentiate his work from the music of the 1995 Tim Robbins movie. It incorporates local color and hymns, but it mostly discordant, and at key moments, cacophonic. One of its quieter moments is the meditative quartet of the victims’ parents (Wayne Tigges, Talise Trevigne, Lauren Decker, and Allan Glassman), which contrasts with the often-frantic music surrounding Joseph de Rocher and his climatic last walk.

On a stage where nineteenth century melodramatic heroes often butcher each other in escapist drama, Dead Man Walking is by far the Lyric’s darkest work since The Passenger. It’s not the kind of thing a company can fill its season with, although the opening night drew a crowd that was noticeably younger than usual. Jack Heggie attributes the opera’s success to its refusal to lecture; he acknowledges that this debate has been going on for a long time, and this story has been told before. Joseph de Rocher (an amalgamation of a couple of men Prejean counseled) is a frustrating figure. In this production, he has several Nazi tattoos nobody ever comments on but which suggest he has committed numerous atrocities besides the one he’s being put to death for and that his evil mindset is far more extensive than what Sister Helen is trying to get him to repent of in just three weeks. He admits that making people question his guilt is the last bit of sadistic power he has, but that confessing would also be a horrible blow to his family. The opera doesn’t pretend to know how to handle people like him. But it does demand that people treat the issues it raises with the seriousness they deserve and to be less inclined toward viewing other people as abstractions. It also demonstrates the true potential of this musical form to communicate the most extreme experiences.

Dead Man Walking will continue at the Lyric Opera House, 20 N Upper Wacker Drive, Chicago, thru November 22, with the following showtimes:

November 10: 2:00 pm

November 13: 2:00 pm

November 16: 7:30 pm

November 22: 7:00 pm

Running time is two hours and fifty-five minutes with one half-hour intermission.

Performances are in English with supertitles.

The Lyric offers parking deals with Poetry Garage at 201 W Madison St. if inquired about in advance. Tickets start at $39; to order, visit LyricOpera.org or call 321-827-5600.![]()

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Dead Man Walking.”

More Stories

“Henry Johnson”

“Scary Town” reviewed by Frank Meccia

“Translations”