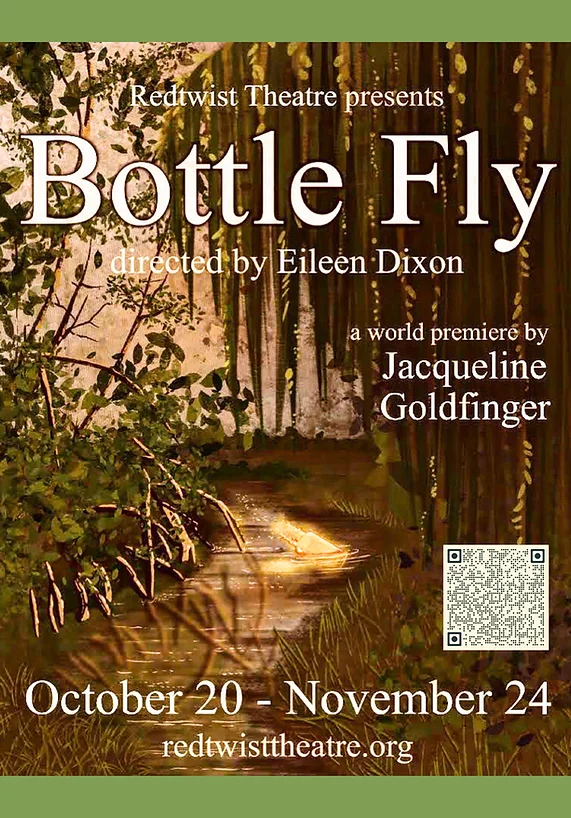

***The world premiere performance of Jacqueline Goldfinger’s “Bottle Fly” is good but not as powerful as it could have been. The advance piece states that the play is “a beautiful depiction of queer survival in the Everglades capturing the many-layered dynamics of race, poverty and bigotry that are sun-baked into life in South Florida.” The show contains some powerful acting, such as Laura Sturm as Rosie, Johnny Garcia as her husband Cal, and especially Rebecca VandenBos as K (and not Kay). VandenBos can boast of a fine singing voice and does a wonderful job grunting (instead of speaking) during the moments when she plays a mute. What is unique about this tale is that Rosie and her husband have chosen to defy prevailing cultural norms by housing an openly lesbian couple.

***The world premiere performance of Jacqueline Goldfinger’s “Bottle Fly” is good but not as powerful as it could have been. The advance piece states that the play is “a beautiful depiction of queer survival in the Everglades capturing the many-layered dynamics of race, poverty and bigotry that are sun-baked into life in South Florida.” The show contains some powerful acting, such as Laura Sturm as Rosie, Johnny Garcia as her husband Cal, and especially Rebecca VandenBos as K (and not Kay). VandenBos can boast of a fine singing voice and does a wonderful job grunting (instead of speaking) during the moments when she plays a mute. What is unique about this tale is that Rosie and her husband have chosen to defy prevailing cultural norms by housing an openly lesbian couple.

Rosie and Cal are both barkeeps in a small tavern in a rural area of Florida. They take in “money guests” in order to survive. And they have taken in Ruth (Shannon Leigh Webber) and Penny (Shaina Toledo), a lesbian couple who reside in an attic above the bar. We find out later that Rosie knows Penny’s family and they have an issue with her being a lesbian, which is why Rosie has rented a room to her and her lover. The couple seems to get along nicely until they have a furious argument. It is clear that they are very different people from the onset: Ruth being well-educated and Penny no so much. But that never seemed to make any difference—until now.

At the beginning, I couldn’t figure out exactly what the relationship was between Rosie and K. I first thought that K might have been a love interest of Rosie’s (since she called her a “real guest”), but later we find out that she’s her adopted daughter. K was apparently in a bad family situation (since she was an unwanted child), and that’s why Rosie and Cal previously accepted her as their own. I wasn’t certain if her inability to speak was a disability from birth or the result of living through trauma. But it doesn’t make a difference. The only time she speaks is when she breaks the fourth wall and addresses the audience. In fact, a lot of this show is devoted to asides, where various characters tell us about their backgrounds and how they feel about their personal situations. What is notable is that Rosie is comfortable enough with the lesbian couple that she lets K pal around with them.

Yet a show which is intended to shine a light on a lesbian relationship doesn’t seem to pack the punch that it should. This is probably in large part because audiences in Chicago tend to be more tolerant of “gender splendor” as compared to more conservative parts of the country. Basically, the relationship between Ruth and Penny doesn’t seem shocking to us. Other than Ruth and Penny having a major argument between them, the characters are much too stagnant. The display of tolerance in a cultural backwater thus becomes the gist of the story. To my mind, however, the tale needs to be more than just a snapshot of life and should feature a stronger plot.

While the advance piece promises us a racial dynamic as part of the play, I didn’t notice this at all. That begs the question as to whether K is supposed to be a black woman in the context of the story or not. What I did take note was that the songs that K would sing were those initially popularized by black women performers, such as Kate Smith’s “Dream a Little Dream of Me”, Billie Holiday’s “You Go to My Head”, and Ella Fitzgerald’s “Honeysuckle Rose.” The emphasis on honey and honeybees in connection with a loving relationship cannot be missed as well as the analogy where Ruth and Penny have a common interest in raising bees. Yet I wanted to see Ruth and Penny talk about their goals and ambitions and their plans for taking their relationship forward, as in the case of any two people who consider themselves to be a couple. I was waiting for some inciting incident to occur that might change all of the characters for the better or the worse, like a flood or a fire or a bankruptcy or, better yet, social unrest among conservative neighbors within the community. But this never happened.

While the play is set in South Florida, it could have theoretically been anywhere in rural U.S.A. In other words, there is nothing particularly regional about this story, except perhaps Cal’s mode of employment. But perhaps this is a good thing, because people from all parts of the country might be able to relate to it. This became apparent by the statement from artistic director Dusty Brown on opening night. He told the audience just how much the script resonated with him the moment he read it two years ago. Then too, director Eileen Dixon explained in the playbill how she was originally from a “poor, rural, small town in North Carolina [where] there weren’t any ‘out’ gay people, let alone openly-queer women.” And so this script was very meaningful to her too. That being said, too many aspects of the show had me confused, and the writing needs to be clearer.

I liked Rose Johnson’s realistic scenic design: We see a fully-fashioned bar with wood paneling throughout. Prop design by Leo Bassow adds to the illusion with hanging lights and pictures, stools, a countertop, and of course, a ladder leading up to the attic. Tables line the sides of the storefront theatre near the stage, with some ensemble members and members of the creative team seated as patrons. This is a very nice touch. Sam Anderson’s lighting design, Angela Joy Baldasare’s sound design, Madeline Felauer’s costume design, and Caroline Kidwell’s music direction are all right on target.

Since some of the language used can be coarse and sexually explicit, it does have a shocking quality that you ought to be prepared for.

An audience already familiar with queer stories and the existence of openly queer relationships might miss just how poignant this show can be to those who have had to hide their sexual orientation or gender identity. Although the characters talk a bit about the meaning of collecting a fly in a bottle and then releasing it, I can only speculate about what the metaphor means: namely, that we all are prisoners of circumstance. Far too many people are forced to hide their little bright lights inside of themselves. In the context of the show, release from the bottle likely has to do with being free to express love, affection, and sexual desire as authentically and fully as possible.

“Bottle Fly” is playing through November 24, 2024 at Redtwist Theatre, 1044 W. Bryn Mawr Avenue, in Chicago.

Tickets:

All Friday performances are “Pay What You Can”

Performance schedule:

Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at 7:30 p.m.

Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at 7:30 p.m.

Sundays at 3:30 p.m.

Understudy Performances

November 3 at 3:30 p.m.

November 14 at 7:30 p.m.

Accessibility Performances

November 1 at 7:30 p.m.

November 10 at 3:30 p.m.

November 22 at 7:30 p.m.

For more information and to purchase tickets, go to: https://www.redtwisttheatre.org/bottle-fly-1.

For general information and a list of their other offerings, see https://www.redtwisttheatre.org/.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Bottle Fly”.

More Stories

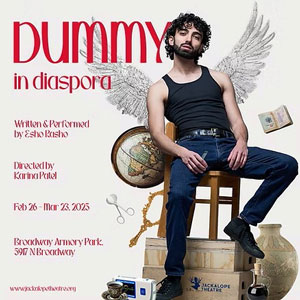

“Dummy in Diaspora”

“The Magic School Bus: Lost in the Solar System”

“February House” reviewed by Julia W. Rath