rating=4] Taking Anna Karenina, one of world literature’s wordiest and most complex novels, and adapting it into the purely visual and physical form of ballet is a tall order. It’s been done a few times, but when the Joffrey Ballet did it in 2019 in a co-production with The Australian Ballet, it was the first time in the company’s history that they commissioned an entirely original score. It’s understandable why: a project like this requires a very definite artistic vision, which is easier when you don’t have to accommodate music that was made for someone else’s concept. The Joffrey is now remounting Yuri Possokhov’s choreography for Anna Karenina, but in their new home at the Lyric Opera House, in a production that is as grim and cerebral as it is elegant, and when the story is, perhaps for the first time in a long while, overtly and undeniably political.

rating=4] Taking Anna Karenina, one of world literature’s wordiest and most complex novels, and adapting it into the purely visual and physical form of ballet is a tall order. It’s been done a few times, but when the Joffrey Ballet did it in 2019 in a co-production with The Australian Ballet, it was the first time in the company’s history that they commissioned an entirely original score. It’s understandable why: a project like this requires a very definite artistic vision, which is easier when you don’t have to accommodate music that was made for someone else’s concept. The Joffrey is now remounting Yuri Possokhov’s choreography for Anna Karenina, but in their new home at the Lyric Opera House, in a production that is as grim and cerebral as it is elegant, and when the story is, perhaps for the first time in a long while, overtly and undeniably political.

This Tolstoy adaptation, with a libretto by Valeriy Pecheykin, presents a Russian aristocratic world that is, at its most striking moments, cold and gothic. Projection designs by Finn Ross emphasize monumental architecture and skies that blend snow with smog. The music by Ilya Demutsky is modern but not out of place for the period. Conducted by Scott Speck, it glides us along in a world driven by magical visions, fever, and morphine. Judiciously used scrims sometimes further filter our perception and the shadows are heavy. Not that it’s all gloom and doom; the hapless Kostya Levin (played by Yoshihisa Arai at the performance this reviewer attended) got a laugh from the audience early on for his attempt to woo Princess Kitty (Anais Bueno) in a masterful bit of physical comedy. The occult-obsessed Countess Nordston (Jeraldine Mendoza) jerks and skitters like something that should have more legs. But amid these characters, the solid, commanding grace of Count Alexey Vronsky (Alberto Velazquez) is undeniably enticing. Despite being married, Anna Karenina (Victoria Jaiani) doesn’t just throw herself at him; she coils all the way around him and climbs up and down like a cat.

One of the distinctive qualities of Possokhov’s take is the heavy emphasis on Anna’s addiction to opioids. She is first given them by a doctor when she suffers from a fever, which in the novel is related to a miscarriage that was probably caused by her affair with Vronsky. However, if she had been pregnant by her husband, Alexey Karenin (Dylan Gutierrez), the result would have been exactly the same, and it seems her addiction is a significant factor in the deterioration of her relationship with Vronsky and Karenin’s decision to limit her contact with their son. (Social stigma against Anna for the affair itself is downplayed to the point of being omitted.) Another important point of emphasis is Anna’s complex feelings for her husband. Although their interactions are stiff, the second act opens with Anna, thinking she is dying, imagining herself dancing with both Alexeys. In this sequence, the men mirror each other’s movements, and she responds to them equally. A lot had to be cut for this adaptation, but one thing that was retained was Karenin’s frustration with getting his signature immigration reform legislation passed, and there is a whole scene of him attempting to wrangle votes through increasingly frantic movements. It ends with him getting mobbed on the floor of the Russian legislative chamber in the ballet’s clearest example of violent social pressure.

It’s always an irony in adaptations of Anna Karenina to visual mediums that they tend to be opportunities to revel in imperial aristocratic fashion, when Tolstoy is usually interpreted as trying to decry that sort of thing. The costume design by Tom Pye does display nineteenth century finery, but Pye also designed the sets, which, for a few flats and frames, are remarkably oppressive. The death of a worker in an industrial accident very early on is our only clear look at any of the urban working class and it’s heavily sanitized, and yet, nobody besides Levin and Kitty really seem happy, and Anna is clearly desperate to feel anything. When the show opened in 2019, it is likely that Anna’s medically induced addiction and the toll Karenin’s political activities were taking on his emotional health and marriage were more clearly meant to be the focus. Today, you might reasonably ask whether this was the story the present moment demanded. (There have been Ukrainian protests at performances.

The show opens with a message of support for Ukraine and a projection of Ukraine’s national colors, along with a selection from the late composer Myroslav Skoryk, who was the artistic director at the Taras Shevchenko National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine in Kyiv. But the program note indicates that some of the Russian creative leads still have works in development at the Bolshoi, so your mileage may vary.) Levin’s final dance solo seems more like a moment of self-actualization and a dignified conclusion to his character arc than a romanticization of the Slavic Orthodox rural community as somehow free of the city’s social pressures; its musical tone is deeply melancholic. Fans of Anna Karenina may be pleased to see any highly skilled adaptation that puts a new spin on the story, but for those who don’t know it well, the ballet is an easy introduction.

Anna Karenina will continue at the Lyric Opera House, 20 N Upper Wacker Drive, Chicago, thru February 26, with the following showtimes:

February 24 7:30 pm

February 24 7:30 pm

February 25 2:00 pm and 7:30 pm

February 26 2:00 pm

Running time is two hours and fifteen minutes with one intermission.

Tickets start at $36; to order, visit Joffrey.org or call 321-386-8905.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click “Anna Karenina.”

More Stories

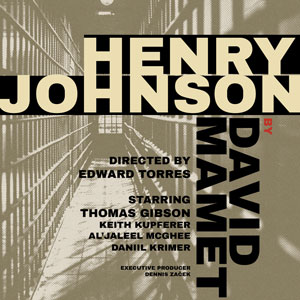

“Henry Johnson”

“Scary Town” reviewed by Frank Meccia

“Translations”