Editor note: this one man play was here in September, left, and has returned. Some minor changes were made.

*** Back in December 1976, I was sitting on a crowded train going through Europe. I happened to meet two other Americans my age in our compartment, and we got to talking. One of them said, “You know, all the biggies died this year: Mao Tse Tung, Zhou Enlai, and Mayor Daley.”

*** Back in December 1976, I was sitting on a crowded train going through Europe. I happened to meet two other Americans my age in our compartment, and we got to talking. One of them said, “You know, all the biggies died this year: Mao Tse Tung, Zhou Enlai, and Mayor Daley.”

Mayor Richard J. Daley’s powerful legacy in Chicago and the Democratic Party thus provides the framework for a contemporary play about his nemesis: political reporter and commentator Mike Royko. In this one-hander, written and performed by Mitchell Bisschop, we are introduced to the famed newspaper columnist and his writings on local politics, government, sports, and what-have-you during his forty-year career with the “Chicago Daily News”, the “Chicago Sun-Times”, and the “Chicago Tribune.” In the course of his nearly 8,000 columns from the 1950s through the 1990s, Royko promoted the decency and fairness of the common man while lambasting crooks and cronies and uncovering partisan scandals. While perhaps being best known for his 1971 book “Boss” about the Daley political machine, it was his wry sense of humor which helped gain him readership, giving him the reputation of being the one of the finest reporters that Chicago has ever produced.

The story is mostly told as a chronological narrative where Royko’s personal life is described in parallel with the events going on in the city and the world at-large.* His toughness was bred into him at a young age while growing up in a Polish neighborhood on Chicago’s Northwest Side. He began working at a bar at age 13, where he met all sorts of patrons and listened to their stories about the meaning of clout. Additionally, he knew what it meant to run his mother’s cleaning business, where building inspectors could come in at any moment and shake down an owner for a bribe. The show pretty much opens with Royko’s 1976 column criticizing how Mayor Daley bowed to the wishes of mafia kingpin Sam Giancana by providing round-the-clock police protection for Frank Sinatra. Unlike the mafia whose nefarious acts were kept well-hidden, Daley’s claim to fame was having his flunkies carry out all manner of corruption out in the open, making it a part of daily life, all in the service of “the city that works.”

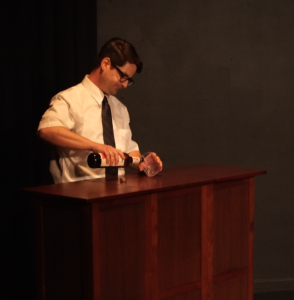

It is amazing to watch Bisschop as Royko going practically non-stop during this two-hour show (which includes an intermission). And there are so many lines to remember! Yet a shorter, sharper 90-minute one-act performance would have served better. Having said that, plot points in this script are generally quite good, and the story sails nicely from one set of anecdotes to the next. My guest got into the funny lines; I got into the politics. Act One appropriately ends with the death of Royko’s first wife Carol and the fact that he takes a much-needed break from writing. When the plays resumes, it is with a certain amount of wit. That’s what I was waiting for: more of Royko’s wry humor and cynicism.

There were moments when I would have liked to have seen more of Royko the reporter. In the 1950s, he would have worn his fedora and raincoat and pull out a pad of paper to take notes on the various people he was writing about. In this respect, the way the set is designed is a bit too confining: We might see Royko sit at his desk and then at a bar, or he might stand and address the audience. It would have been good to see him with a streetscape behind him gathering facts and information as well. He could have read his own notes to himself, which would have added to the reality of being a working newspaperman. That said, I especially liked the prop design, featuring a desk full of lots of papers and a telephone, etc., and of course, a typewriter. It would have been great had Royko type a few words and then literally pull the paper out from the typewriter and read from his nascent column, perhaps to rephrase a sentence or move around a paragraph or two. I wanted to see the journalist struggle to get just the right turn of phrase or get his facts just right.

My biggest problem with the show, however, is that I was spending too much time comparing the Royko of my memories to the man on stage, but they never became one and the same. Throughout the performance, it wasn’t clear whether Royko was addressing his readers or an audience of those interested in buying his books or whether he was simply talking to himself or reminiscing about his life experience. I wondered all throughout whether he was taking his lines from the books he had written or directly from his columns over the years. Or perhaps the verbiage in the monologue was new and novel?

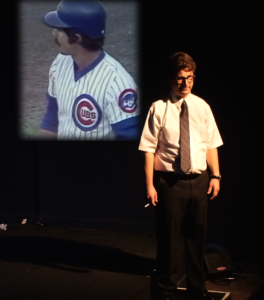

Much of this confusion could have been easily remedied by the projection design, which was not being used to its maximum advantage. Instead of so many cityscapes, I would have liked to see slides of specific columns written by Royko from the various newspapers. Dates attached to each of these could have been flashed in large print. Near the end, for example, there’s a discussion about how Rupert Murdock bought out the “Sun-Times” and reran Royko’s old columns and said he was on vacation. These columns could have been displayed adjacent to the contemporaneous ones from the “Chicago Tribune”; that would have been impactful and would have added to the show’s humor. Showing slides of his book covers or slides of book chapters would have helped when paragraphs from them are being quoted. Moreover, watching the projections on five different screens works okay much of the time but not always. Sometimes faces are cut in half and writing is cut off. I got tired of seeing all those slides of Venetian blinds to indicate that Royko was working in his office. Having said that, the video choices are generally very good. I especially liked seeing the footage from the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, which elevated Mayor Daley as a figure on the national stage. I also liked the projection design that showed smoke, considering that smoking clearly took place during that era.

Sound design could have been better, especially in balancing out what Bisschop was saying in relation to the various sound effects. For example, whenever Royko receives a phone call or if some announcement is made, the sound is much louder than it needs to be. Also we can notice a bit of a costume change between Acts One and Two. Most importantly, we see Bisschop wearing different eyeglasses. Now having said that, a one-act version could have the glasses change from one scene to the next, from one era to the next, so as to more accurately match current fashions.

In all, we see Royko as a public figure who witnessed a generation of change in Chicago politics, culture, and population, not to mention the evolution of Chicago’s skyline. It was not that good government replaced the political machine but that the power once held by City Hall had become somewhat more decentralized as city politics largely shifted from the Irish, the Italians, and the Poles (i.e., the white ethnics) to the black and Hispanic communities. In the course of following a succession of mayors and the City Council, Royko ultimately concluded that Mayor Richard M. Daley no longer commanded the same power and veneration that his late father once did.

By and large, Royko’s columns took many of these societal and institutional changes and brought them down to the individual and neighborhood level, such as his most famous column from 1966: about how Chicagoans Mary and Joe are reunited with their baby at Christmas after urban renewal orders their building torn down. I realize that Bisschop had to pick and choose from among a vast subject matter in writing this play, but what was missing was the “laugh out loud” humor that I associate with Royko’s style of writing. Perhaps rather than spending so much time on the 1967 unveiling of the Picasso statue across from City Hall, a bit more could have been spent on the journalist’s craft.

“Royko: The Toughest Man in Chicago” has been extended from its original September run through December 22, 2024. Director Steve Scott is new to this production, which is playing at The Chopin Theatre, 1543 W. Division Street, Chicago.

General admission tickets are $60 ($65.09 with a service fee)

Group tickets are $40 ($43.89 with a service fee)

Performance schedule:

Performance schedule:

Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays – 7:30 p.m.

Sundays – 3:30 p.m.

For more information about this show, visit: toughestmaninchicago@gmail.com or call 847-920-7714.

To purchase tickets, see: https://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/6294348#:~:text=For%20over%20three%20decades%2C%20Royko%20captured%20the%20spirit,fearlessly%20tackled%20corruption%20and%20championed%20the%20everyday%20citizen.

For more information about the Chopin Theatre and their other offerings, call 773-278-1500 or (cell) 773-396-2875; or email info@chopintheatre.com.

*Note that the timeline in the printed program is very useful in grounding the performance. But some of that information should have made it into the show itself, without the narrative sounding like a documentary.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Royko: The Toughest Man in Chicago”.

More Stories

“Falsettos”

“Magic in Session” reviewed by Paul Lisnek

“The Marriage of Figaro” reviewed by Jacob Davis