** The world premiere production “Stokely: The Unfinished Revolution” doesn’t do justice to the legacy of Stokely Carmichael. Stokely was a towering presence in the Black Power Movement of the 1960s. Born in Trinidad and growing up with the Civil Rights Movement and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement, his consciousness was gradually raised about the second-class citizenship of black people in the United States. Outspoken and politically active, he became a popular speaker for anti-Establishment causes. A polarizing figure, he advocated violent revolution so that African Americans might gain better foothold in society, improved opportunities for jobs and income, equity in politics, and much more.

** The world premiere production “Stokely: The Unfinished Revolution” doesn’t do justice to the legacy of Stokely Carmichael. Stokely was a towering presence in the Black Power Movement of the 1960s. Born in Trinidad and growing up with the Civil Rights Movement and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement, his consciousness was gradually raised about the second-class citizenship of black people in the United States. Outspoken and politically active, he became a popular speaker for anti-Establishment causes. A polarizing figure, he advocated violent revolution so that African Americans might gain better foothold in society, improved opportunities for jobs and income, equity in politics, and much more.

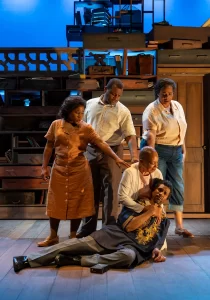

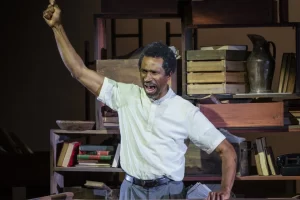

The incredibly versatile and talented Anthony Irons excels as Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture). However, despite his wonderful acting and that of a delightful supporting cast, a choppy and often confusing story does not live up to expectations. Far from being a straight-line biography of Stokely’s life and accomplishments, it’s a mishmash of past and present, vignettes and reflections: all in a stream-of-consciousness narrative where hot button issues from the 1950s and 1960s have been watered-down in favor of focusing on Stokely’s relationship with his mother (Wandachristine as Mabel Carmichael a/k/a May Charles).

Written by Nambi E. Kelley and directed by Tasia A. Jones, the play has an overarching premise: Stokely (a/k/a Kwame) wants to memorialize himself at the point of his death and chooses to make a tape-recorded account of his life’s highlights. At the same time, he wants to reconcile with his mother—if not outright understand her—and learn the reasons why she left him at the age of seven when she emigrated to the Bronx. Even though the young boy was placed with his grandmother and aunt, he felt unloved nevertheless, as if he had done something wrong. These circumstances were so painful that it affected practically everything he did in his life from then on. Considering its major emphasis on the tensions between mother and son, the play would have been better titled “Stokely: The Unresolved Relationship.”

One major problem with the script is its unrelenting shifts in time and space, making the story as presented much too jerky and uneven. We initially see Stokely as an adult in his waning years, followed by being a seven-year-old child (played by the same actor). Then he goes back to being an adult, then a child, then a teen, and so forth. While remembrances from 20, 30, and 40 years prior come to his mind in an instant, the focus always returns to his early childhood memories. As a result of tons of flashbacks and flashforwards, it becomes hard to follow how Stokely got where he did to become such an important force in African American politics and history. There needs to be a clearer chronology so as to understand why we ought to be following his life story in the first place. Instead, all this back and forth through the years only serves to weaken the narrative and distances us from the characters, making them appear more stagnant than they should be. The result is that we can potentially lose not just the thread of the story but also empathy for them and the larger cause.

Furthermore, the supporting actors play almost too many characters: all from different times and places within Stokely’s life and at different points in their own lives. When multiple roles are played by the same actors frequently in subsequent scenes, it becomes weird to see someone who is dead or long gone popping up again as a different character. One example is when Kelvin Roston, Jr. plays Stokely’s father who dies in one scene and is immediately resurrected as Martin Luther King, Jr. in the next. Other cast members include Dee Dee Batteast as Cecilia Carmichael/Ensemble and Melanie Brezil as Tante Elaine/Ensemble. Note that their collective voices blend together beautifully as they sing soulful songs in several places during the show.

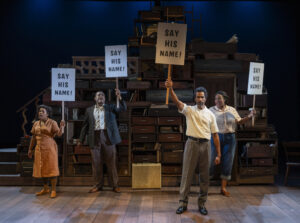

Perhaps more importantly, while we witness black advocacy all throughout the performance, what is largely absent is white resistance. The show becomes mostly like watching a one-sided argument. We see some debate between the possible use of non-violent versus violent means to achieve equality and equity, and the names of A. Philip Randolph, Malcolm X, John Lewis, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Martin Luther King, are included to exemplify how African Americans fought to achieve civil rights. But to make this show work, there must be a dynamic of confrontation between blacks and whites. We need to see more white initiated violence upfront and personal in order to create a stronger motivation for the Black Power Movement. More overt racism and hate on stage will allow us to grasp more fully what the battle is about and how high the stakes are—and to comprehend exactly where Stokely fits in as a political activist creating a revolutionary movement. Yes, there is a scene with the throwing of grenades against protestors, and we also see Stokely going to jail. We also observe him Stokely participating in SNCC (the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) and we learn of his becoming the honorary head of the Black Panthers. In fact, one of the best segments is the “Say Their Name” scene. But the play should have more clearly laid out the historical groundwork for all of this rather than constantly interrupting with autobiographical recollections that may not be all that significant to the audience.

Yeaji Kim’s versatile set allows us to use our collective imagination to envision Stokely’s writing den in Conakry, Guinea, in 1998, as well a prison, a schoolroom, sites for rallies, and so on. Above all, this moveable set nicely captures the desegregation of the lunch counters. Costume design by Gregory Graham could not have been more appropriate for the era, and I especially liked the traditional attire worn by Stokely’s South African wife Miriam Makeba. Ruben D. Echoles hair and wig design works well in allowing us to differentiate among the various female characters. But perhaps the best element of the show is the lighting. If not for the absolutely brilliant work by Daphne Agosin (which should win all sorts of awards), this play would have been a complete disaster. Without all of the quick changes from one style of lighting to the next and from one color temperature to the next, the audience would have been totally lost trying to follow the story. For example, those scenes towards the end of Stokely’s life when he hosts his mother are lit using orange-yellow white lights (2200K); then there are those scenes when he is a child growing up which use bluish white lights (7500K), and there are scenes when his grandmother holds him tight as a very young child, when she tells him to breathe after his mother leaves for America; here the harsh purplish lighting (12,000K) could not have been better. Also kudos to dialect coach Sammi Grant, who imparted Trinidadian accents to Stokely’s mother, grandmother, and aunt.

Despite all the drama, the play needs to be more challenging and explosive. The portrayal should have engendered a stronger response from the audience than it did, and we should have been sitting on the edge of our seats. Yes, the line “I can’t breathe,” is spoken by Stokely more than once in the show, obviously reminiscent of George Floyd’s now well-known outcry as he was strangled to death by Minneapolis police in May of 2020. But the audience should not necessarily have to draw on our personal knowledge of Jim Crow and race relations to understand this play. The show should have presented more background about the history of the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panthers and more speeches about how morally wrong it is when people are exploited and their rights compromised. The story ought to make plain why non-violence was insufficient in the fight against prejudice and discrimination, other than the characters mostly having discussions about it. It is important to see, hear, and feel what the people in the 1950s and ’60s went through, because it is this reality that launched Stokely’s militancy in initiating social action. We need to know why a substantial portion of the black population at the time followed him and felt that revolution was important to pursuing freedom and justice for all. Now after firmly establishing this sense of political consciousness from the past, the narrative could then appropriately plunge these ideas into the present-day: hence the concept of an unfinished revolution.

Finally, it is Stokely’s life in the larger scheme of history that makes the friction between him and his mother start to become interesting to a wider audience. When the script fails to lay down a lot of this groundwork and keeps shifting the timeline and characters, the only thing we have left with is the constant rehash of how much an impressionable young child eventually accomplished what he did because of his violent reaction to the seeming loss of a mother’s love.

“Stokely: The Unfinished Revolution” is playing through June 16, 2024, at Court Theatre, 5535 S. Ellis, Chicago.

Tickets: $56-$88.

Student, group, and military discounts available.

Performance schedule:

Performance schedule:

Wednesdays, Thursdays, Fridays – 7:30 p.m.

Saturdays and Sundays – 2:00 p.m. and 7:30 p.m.

No matinee performances on Saturday May 25th and Saturday, June 1st.

Accessible performances:

Touch Tour on June 15, 2024 at 12:30 p.m.

Audio Description and ASL Interpretation on June 15, 2024 at 2:00 p.m.

Open Captioning on June 6, 2024 at 2:00 p.m.

For more information and to purchase tickets, go to: https://www.courttheatre.org/season-tickets/2023-2024-season/stokelythe-unfinished-revolution/. or phone the Box Office at 773-753-4472, or visit the box office at 5535 S. Ellis Avenue, Chicago.

For general information about Court Theatre and to learn about their other offerings, go to

https://www.courttheatre.org.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com , go to Review Round-Up and click at “Stokely-The Unfinished Revolution”.

More Stories

“The Last Five Years” MILWAUKEE

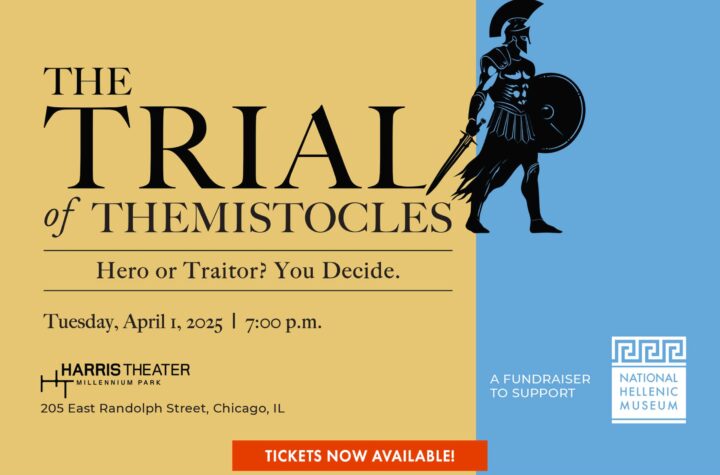

“The Trial of Themistocles” reviewed by Julia W. Rath

“Titanique”