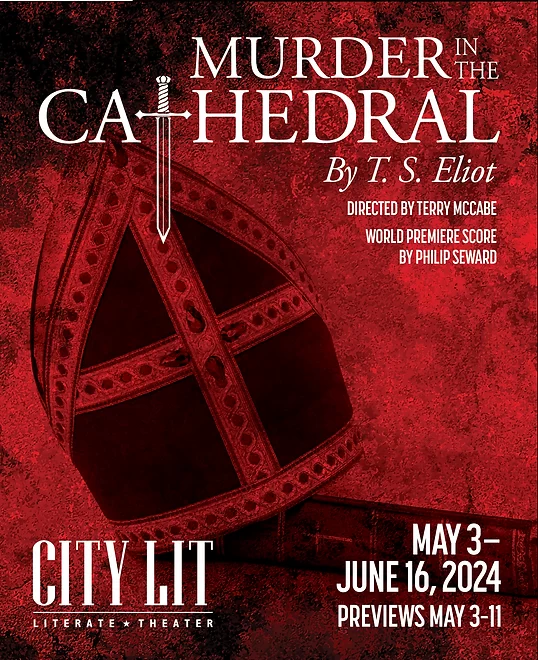

*** “Murder in the Cathedral” is a story about the martyrdom of Thomas à Becket, written by T.S. Eliot in 1935. James Sparling makes for an extraordinary Becket: vibrant, convincing, and full of life. Yet despite his aura of positivity, Becket is obsessed with thoughts of holiness, pureness, and ascetism and subsequently asserts his undying wish to become a Christian martyr for the faith.

*** “Murder in the Cathedral” is a story about the martyrdom of Thomas à Becket, written by T.S. Eliot in 1935. James Sparling makes for an extraordinary Becket: vibrant, convincing, and full of life. Yet despite his aura of positivity, Becket is obsessed with thoughts of holiness, pureness, and ascetism and subsequently asserts his undying wish to become a Christian martyr for the faith.

Having spent seven years of self-exile from his beloved Canterbury Cathedral, Becket returns as Archbishop in 1162. But he carries baggage with him from his years as Lord Chancellor and feuding with King Henry II about the necessity of the English king to become subservient to the Pope in Rome. At issue is the principle of the Divine Right of Kings, which Henry wants to enforce even at the cost of spilling Becket’s blood. For his part, Becket feels that he has every right to assert the primacy of the Church as compared to the primacy of the Kingdom. Death is not something to be feared. His soul could never be damaged as long as his faith was strong and his beliefs remained pure. He believed that people ought to be subservient to the religion and thus felt that the other priests in the church did not have a strong enough faith such that they feared his demise. The result is Becket’s murder by four of the king’s knights in December 1170.

One of the best aspects of the play is its perfect staging: I loved the set using an actual church sanctuary (namely that of the Edgewater Presbyterian Church), which only adds to the story’s mood and realism. The audience is also upfront and close to the action as the portable seats are set up in a V-formation with a line at the bottom. Thanks to the fine direction by Terry McCabe, the characters engage with each other on the sanctuary floor and also on the altar, and they enter using various doors and hiding places. Superior lighting design by Mike McShane draws attention to all the right elements. I enjoyed the uses of the piano for the music that deals with present circumstances and with the action taking place; then too, there is the pipe organ for all the sacred music. Here the work of music director Mark Weston is wonderful. Accompanist Jacob Adams on keyboards cannot be excelled, plus there is Anna Bundy on chimes. Graphic design by Lisa Maraldi is notable, principally the red postcards advertising the show.

I especially liked the authentic 12th century garments, which are the creation of costume designer Patti Roeder. My favorite is the Archbishop’s black with red trim caftan which holds secret red ribbons which Sparling pulls to indicate the drawing of blood—just before Becket dies in the middle of the floor. (Note that Sparling’s costume changes are amazing, from the simple to the complex!) The men’s priestly garments are particularly great, and I adored the dresses that the chorus of four women wear. Just note that during this time period, women were considered second-class citizens; and in this show, they define their roles as scrubbers and scourers. As the four sing their mournful songs, they wonder what might happen when Thomas makes his return to Canterbury. How might all of their lives change?

In addition to Becket (Sparling), other characters include the chorus of women (Katarina Bakas, Kara Chandler, Sally Olson, and Isabel Schmitz); the priests (Stephen Fedo, John Blick, and Joel Thompson); the tempters (Sean Harklerode, Robert Howard, and Varris Holmes); and the knights (Harklerode, Howard, and Holmes plus Zach Kunde, who also plays the messenger).

Despite wonderful acting, marvelous directing, well-executed music, and great costumes, the various components in this play don’t add up as they should. The plot is relatively simple, but all the pontificating and singing can be more than an audience member can absorb at once. I found that the moment I examined one idea that Thomas or a tempter would spout, the next idea would come, and I’d get mired in the details, making it difficult for me to follow portions of the story. When I found myself working too hard, the first half became somewhat somniferous. But the second half contained more action and was thus more engaging.

Philip Seward’s world premiere score has some challenges to overcome. By putting T.S. Eliot’s poetry to song, Seward inserts an additional element of operetta that sometimes distracts from the main point of the story. Basically, the nuances and finer points of the discussion about religious faith and personal demeanor become harder to follow when we have to dissect the meaning of so many song lyrics. Especially when the four sopranos sing together, the words are sometimes hard to make out, even though all the singing voices are very good when taken separately. Incidentally, since my guest and I were sitting in the first row, we both found ourselves studying the vocalists’ mouths to fully understand all the words that they were singing.

Having some previous familiarity with the underlying history of this time period can be helpful while watching the performance. Years ago when I was in graduate school, I wrote a paper about the misunderstanding of power and authority relations between Henry II and Thomas Becket. I asserted that the ultimate authority for both was God but that each saw their relationship to God very differently and this disagreement colored their relationship. Conflicting ideologies largely fueled the dispute between them, not to mention differing ideas about political and religious will and domination. I’m including this bit of personal history, because the very last part of the show reminded me of it. This is where Eliot has the four knights cast aside their 12th century garb and don modern attire. The lead knight/attorney explains that Americans would want more of a rationalization for the murder. The group of four largely defend Becket’s slaughter by claiming that the archbishop wanted to become a martyr; to put it bluntly, the murder becomes his own fault. This segment is a takeoff on Eliot’s original text, where the four men address an English audience and claim that Becket was not the underdog as presented in the play. I hate to argue with a classic script, but this portion seemed unnecessary and almost patronizing.

My suggestion is for an audience member to turn to page four of the program, where there is a brief summary of this famous murder (but no, it’s not a libretto). Other resources include the handout entitled “Becket, T.S. Eliot and Murder in the Cathedral” provided by the Friends of the Edgewater Library, which is available at the entrance to the church. Finally, the more comfortable the audience is with listening to British accents, the more comprehensible the play is. Kudos to Carrie Hardin for having all the characters speak in fairly convincing dialects.

What we don’t learn from this performance is the depth of friendship that Henry and Thomas once had for each other. We don’t know whether Henry ever questioned his decision to rid the world of Becket and what his final straw was that led him to dispatch the murderers. What we do know is that Becket questions himself and his purpose throughout—and his suffering and martyrdom eventually lead to his becoming a saint in both the Anglican and Catholic traditions.

There are often reasons why certain shows are not revived as often as one might think they should and specifically why this show hasn’t been produced more often. To my mind, the 1959 play “Becket of the Honour of God” (shortened to “Becket”) better portrays the animosity between the king and the archbishop and provides a more coherent glimpse into Becket’s ultimate sacrifice.

“Murder in the Cathedral” by City Lit Theatre is playing through June 16, 2024, in the main sanctuary (first floor) of the Edgewater Presbyterian Church, 1020 W. Bryn Mawr Avenue, Chicago.

General admission tickets: $34 (plus applicable fees)

Seniors: $29 (plus applicable fees)

Students and military: $12 (plus applicable fees)

Performance schedule:

Performance schedule:

Fridays and Saturdays- 7:30 p.m.

Sundays – 3:00 p.m.

Mondays, June 3rd and 10th at 7:30 p.m.

For more information or to purchase tickets, visit: https://www.citylit.org/

or call 773-293-3682.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Murder in the Cathedral”.

More Stories

“Blue” reviewed by Jacob Davis

“The Secret Garden”

“Yippee Ki Yay” The Parody of Die Hard reviewed by Frank Meccia