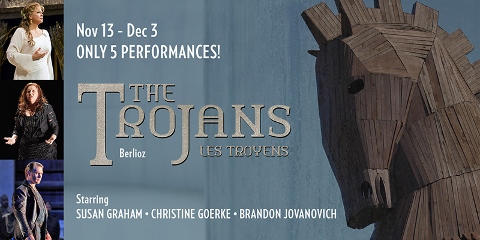

Highly Recommended **** Opera fans have a rare opportunity now to experience a production of composer and librettist Hector Berlioz’s Les Troyens. This nearly five-hour long adaptation of Virgil’s Aeneid is so musically demanding that even Berlioz did not hear it performed within his lifetime—the closest he got was a production of the second half in 1863 which eliminated most of the ballets and was beset by technical and contractual difficulties. Abbreviated concert versions were heard sometimes in the nineteenth and early twentieth century; a New York concert production in 1882 done as part of the May Music Festival had an orchestra of 300 and chorus of 3000, according to opera historian Louise Goldberg. But the complete score was not reconstructed and published until 1969, the hundredth anniversary of Berlioz’s death, and only a few opera companies in the United States have mounted a full production. But under the direction of Tim Albery, with Sir Andrew Davis conducting, and Christine Goerke, Susan Graham, and Brandon Jovanovich in the roles of Cassandra, Dido, and Aeneas, the Lyric Opera’s new production is an unparalleled masterpiece of glorious music.

Highly Recommended **** Opera fans have a rare opportunity now to experience a production of composer and librettist Hector Berlioz’s Les Troyens. This nearly five-hour long adaptation of Virgil’s Aeneid is so musically demanding that even Berlioz did not hear it performed within his lifetime—the closest he got was a production of the second half in 1863 which eliminated most of the ballets and was beset by technical and contractual difficulties. Abbreviated concert versions were heard sometimes in the nineteenth and early twentieth century; a New York concert production in 1882 done as part of the May Music Festival had an orchestra of 300 and chorus of 3000, according to opera historian Louise Goldberg. But the complete score was not reconstructed and published until 1969, the hundredth anniversary of Berlioz’s death, and only a few opera companies in the United States have mounted a full production. But under the direction of Tim Albery, with Sir Andrew Davis conducting, and Christine Goerke, Susan Graham, and Brandon Jovanovich in the roles of Cassandra, Dido, and Aeneas, the Lyric Opera’s new production is an unparalleled masterpiece of glorious music.

In truth, however, Les Troyens’ length and complexity is not the real reason for its rarity, so some adjustment of expectations is in order. Berlioz’s composition is an endless treat, so much so that singling out specific arias or sequences would be reductive. But as a storyteller, Berlioz was shaky even for a nineteenth century opera librettist. Acts I and II, which depict the final days of Troy, are interesting because they are close psychological examinations of the central characters, not the because they form a sword-and-sandal epic, as implied by the opera’s marketing. The third act, in which we meet Dido, queen of the Carthaginians, requires us to accept the usual conventions of pre-Ibsen writing. But then the romance, which is supposedly the heart of the story, flat-lines. And this is, after all, largely a story about Aeneas living comfortably with Dido instead of being a hero. Albery and Davis cut two ballets from Act IV, and there are still two ballets remaining for which Dido and Aeneas are silent observers or not present at all. One of these was meant by Berlioz to be a scene in which Dido and Aeneas take shelter from a storm in a cave during a battle, which establishes their romance, but Albery cuts them from it completely, compounding Berlioz’s tendency to report on crucial bits of action instead of showing them. Their love story is a series of generic declarations until they break up offstage. (This is also the second of three operas at the Lyric this season in which the female lead kills herself because her boyfriend left her.)

So, why the high rating? In the first place, Acts I and II really are quite brilliant, in terms of acting and directing. Eschewing Aeschylus’s shrieking prophetess, Berlioz wrote Cassandra as having to interpret her own visions. Her mournful voice is accented by Berlioz’s beloved horns, and as played by Goerke, she is resigned to her curse to not be believed. She is not, however, resigned to the death of her lover, and Berlioz’s music provides Goerke ample time to go from quivering to agitation, to half-hearted attempts at self-deception, to steely determination to save her fiancé, Chorebus (Lucas Meachem). Speaking of whom, Meachem’s Chorebus is a heartbreaking character. Deeply in love with a woman he believes to be mentally ill, it is clear from Albery’s direction that he has found Cassandra on these ruins many times, and comforted her until she was functional again. But this time, his soothing descriptions of the beautiful Anatolian countryside have a tragic clarinet accompanying the evocative, rolling melodies and bird-like trills. By the time the scene shifts back to within the city walls, it is easy to become misty-eyed at the sight of the grieving Trojans, whose delight at their apparent salvation disappeared in an instant as they realized, while taking their first unlabored breaths in ten years, how much they had lost.

With Acts III-V, it is easy to see what Berlioz was going for, as well as why he missed it. The chorus declares that Dido deserves to be praised because of her beauty, grace, spirit, gods’ favor, and she maintains the love of her people, in that order. What we see is a woman dressed like Margaret Thatcher who shifts uneasily on her feet, keeps her arms within a narrow rectangle except to occasionally throw them in rehearsed, rhetorical sweeps, thanks her people for their labor by promising more hard work, and then distributes ribbons to fishermen, craftsmen, and wheelbarrow pushers like she’s hosting the May Day parade in communist Albania. Her courtiers all wear Nehru jackets or Mao suits. The idea here is that she’s a hard worker who felt unfulfilled without a husband, and her sister, Anna (Okka Von der Damerau), insists the people wanted a male leader anyway, possibly as a ploy to set Dido up romantically. Dido ends Act III standing behind and to the right of Aeneas’s son while Aeneas brandishes a gun centerstage.

With Acts III-V, it is easy to see what Berlioz was going for, as well as why he missed it. The chorus declares that Dido deserves to be praised because of her beauty, grace, spirit, gods’ favor, and she maintains the love of her people, in that order. What we see is a woman dressed like Margaret Thatcher who shifts uneasily on her feet, keeps her arms within a narrow rectangle except to occasionally throw them in rehearsed, rhetorical sweeps, thanks her people for their labor by promising more hard work, and then distributes ribbons to fishermen, craftsmen, and wheelbarrow pushers like she’s hosting the May Day parade in communist Albania. Her courtiers all wear Nehru jackets or Mao suits. The idea here is that she’s a hard worker who felt unfulfilled without a husband, and her sister, Anna (Okka Von der Damerau), insists the people wanted a male leader anyway, possibly as a ploy to set Dido up romantically. Dido ends Act III standing behind and to the right of Aeneas’s son while Aeneas brandishes a gun centerstage.

Again, the music saves it. Berlioz’s score is more fluid than the blaring battle declarations Verdi used to accompany vows of revenge, but the introspective tone is surprisingly conducive to Berlioz’s strength at writing monologs. Act V begins with the Trojan soldier Hylas (Jonathan Johnson) longingly singing the beautiful “Vallon sonore,” which I single out because it is so frequently sampled in other media, and rightfully so. Brandon Jovanovich enjoys an extended moment of glory late in the opera as Aeneas contemplates the ramifications of his decision to leave Dido. That he is still so passionate, technically astute in his singing, and effective in his acting after already performing for several hours is a wonder of the modern stage, and Susan Graham, as Dido in the opera’s final scenes, is absolutely his equal (she’s played the role three times before). Even the script/staging’s final absurdity of dozens of people assisting Dido in her suicide and then crying out in shock when she actually goes through with it can’t negate what Graham accomplishes when she is finally free to perform at full power.

So Les Troyens is a deeply flawed jewel, but still a magnificent one. Michael Black, as always, comes through in a tremendously difficult challenge for a chorus master, and the Lyric’s chorus, like the sixteen leads credited in the program, are accomplished as singers and actors. Designers Tobias Hoheisel with set and costumes, David Finn with lights, the Illuminos collaboration with projections, and Sarah Hatten with wigs and makeup, craft a world driven by Berlioz’s music which can be large enough for dozens of people, yet always feels like the interior of someone’s mind. Perhaps Les Troyens would be performed more frequently, as it was prior to the score’s reconstruction, if conductors were more willing to take liberties with Berlioz. However, the dramatic flaws are arguably inevitable given the kind of music Berlioz wanted to use for this story, and there’s no arguing with the perceptive, inward-looking music. It is right that Les Troyens demands that its audience make a substantial investment in it. Were it disposable entertainment, audience members would find it irritating, but left with no choice but to look for the good, they are likely to find a treasure trove.

“Les Troyens” will continue at the Civic Opera House, 20 N. Wacker Drive, thru December 3, with performances as follows:

“Les Troyens” will continue at the Civic Opera House, 20 N. Wacker Drive, thru December 3, with performances as follows:

Thursday, November 17: 1:00 pm

Monday, November 21: 5:30 pm

Saturday, November 26: 5:30 pm

Saturday, December 3 1:00 pm

Tickets are $149-349; to order, call 312-332-2244 or visit www.lyricopera.org. To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Les Troyens”.

More Stories

“Hamilton” Reviewed by Paul Lisnek “Curtain Call Chicago”

“In Pursuit Of”

“The Brief Wonderous Life of Oscar Wao” reviewed by Paul Lisnek, Curtain Call Chicago