Highly Recommended *****

Among the many wonderful small theatres in Chicago, The Raven Theatre with its large stage; spacious house; excellent ensemble; and dedication to producing plays of the American canon with superlative direction, great acting, and convincing, often period, costumes and sets, stands out. It is a jewel in the crown of Chicago’s vibrant storefront scene. Since I first moved to Chicago in 2008, the Raven’s productions have been so consistently powerful that more often than not after seeing them stage the work of a well-known playwright that particular play immediately becomes one of my favorites, and I often return more than once during the run.

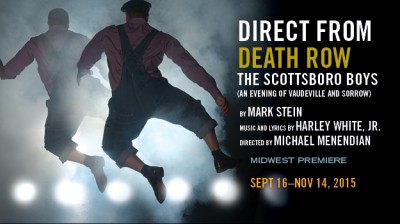

As I arrived for Mark Stein’s “Direct from Death Row the Scottsboro Boys (An Evening of Vaudeville and Sorrow),” I found myself reflecting on the American political landscape rather than the artistry of Miller, Williams, or Foote. Over the past two years, executions have gone horribly wrong in America, leaving victims in excruciating pain for hours before they die, inmates on death row have repeatedly been exonerated, and Texas very well may have put an innocent man to death. Yet the United States Supreme Court shows no inclination to intervene. Simultaneously, black men have routinely been killed by citizens and police officers, usually on slim pretext or for no given reason, always without the benefit of a judge and jury, and often with impunity, heightening (to put it mildly) racial tensions in America.

Enter The Raven Theatre’s current production: a historical drama about nine African American men who were falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931, and who endured imprisonment, including on on death row, and a series of trials before the last of them was exonerated in 1950’s: a serious, true play, about racism and social justice interspersed with vaudevillian musical numbers, performance styles, and techniques. While it sounds like a significant departure from the Raven’s Theatre’s traditional fare, the theatre is able to bring its experienced attention to period detail, powerful acting, and amazingly skilled direction to a story that resonates with our current political and social situation just as effectively as have they done in the past with straightforward American canonical dramas that deal with more exclusively private experiences such as emotional turbulence, familial bonds, and interpersonal relationships.

As the show begins, an ensemble of nine African-American actors take on the role of the Scottsboro Boys, who tell about the events leading up to the false rape allegations against them, their arrest, and incarceration, from prison. As they await the first in a series of seemingly never-ending trials in which guilty verdicts were repeatedly set aside or overturned, they alternatively commiserate, sing (Music and Lyrics: Harley White Jr.), and, comically, spare with one other, sanctioning the play’s music and humor from the outset, and implicitly give us permission to laugh at appropriate junctures. (They are, after all, the chief victims of the gravity and horror of the subject matter.) In prison, Haywood Patterson (a charismatic and highly energetic Kevin Patterson) dominates both the stage and the other prisoners, but he breeds considerable resentment from Olen Montgomery (a bookish Semaj Miller), the young Ozzie Powell (a versatile Anna Dauzvardis), and a number of the other prisoners who feel that Haywood is enjoying his infamy a bit too much.

While the dramatic and vaudevillian scenes are mixed throughout the play’s linear plot, I think potential patrons will benefit from reading about the two techniques separately: first, the darkest parts of the narrative are the horrors of racism, imprisonment, and the threat of execution that these men alone have experienced, and can understand and communicate, and secondly, the more humorous scenes, which center mainly around the white character’s, and contain performances and numbers inspired by vaudeville.

During the play we hear about prison rape, the constant threat of extra-judicial execution, police brutality, near-fatal prison violence, and attempts at escape told by different members of the ensemble. This would probably would be terrifying if we all weren’t too aware of how often these things happened, and sometimes continue to, in the American criminal justice system. Instead, our reaction is more one of shame, despair, and helplessness than outrage or horror, and these are the emotions that the ensemble skillfully evoke and convey, far more than fear, as they talk about being surreptitiously shuffled out the back of prison into a police car, Ozzie slowly going insane in solitary confinement (Dauzvardis’s portrayal of Ozzie’s descent is heart-wrenching), and Haywood’s prison break. (Patterson delivers a monologue so convincingly that one can nearly see the dogs and search party chasing him through the river and forest.)

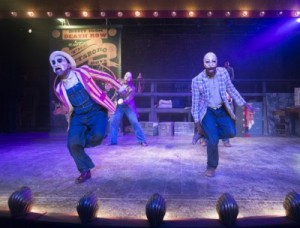

Here, the entire ensemble gives highly credible performances that suggest pain, injustice, sadness, and resignation, but they are also are called on to play white characters in which they apply the bulk of the vaudevillian techniques and traditions. To do so, they were white masks convincingly designed (David Knezz) to represent their particular character’s personality, function, and sometimes, ethnicity. First, there are those white characters, and the black leader of the National Association of Colored People, who are ostensibly trying to help the Scottsboro boys although, at least in Stein’s play, each is also pursuing recognition for their own organization, ideology, or career.

Joe Brodsky (Breon Arzell), the leader of the American Communist Party who secures them at attorney, Sam Leibowitz (Andrew Malone), and Walter White (Brandon Greenhouse), head of the NAACP, who is presumably black, but whose use of a white mask suggests that he has more in common with the Caucasian character’s and their organization than he does with the black men languishing in prison. They each come to the prison and represent themselves and their party in colorful performance numbers and songs inspired by the vaudevillian tradition. Throughout the play, the ensemble plays these white character’s comically with energy and thoroughly enjoyable vaudevillian caricature, including one scene in which the prosecutor General Knight (Semaj Miller) and the defense attorney Sam Leibowitz (Andrew Malone) come together ostensibly to talk about a resolution to the ongoing trials, but end up, at the prosecutors instigation, singing songs from the different ethnic traditions in America, including “Danny Boy” in a celebration of the country’s diversity.

More uncomfortably, the rape trial employs the same techniques of vaudeville and is portrayed just as colorfully and light-heartedly as numbers in which the different advocates meet with the Scottsboro boys in prison. Knight and Leibowitz deliver evidence before a white-masked judge (Tamarus Harvell) and white-masked jury which largely consists of the testimony and cross-examination of the two young white women, Victoria Price and Ruby Bates (Katrina D. Richard and Anna Dauzvardis in white masks).

While no-one doubts that neither women were raped by these men and that Victoria Price gave perjured evidence under oath, there is considerable dispute in contemporary culture about the prevalence, sometimes even the existence, of false rape-allegations, and how those who make them should be treated. Moreover, certain questions asked about Price’s life would no longer be admissible at trial. Bates and particularly Price, who never recanted her false allegations, are mocked more than any of the other characters in the play in scenes outside, and inside, of the courtroom, and Dauzvardis and Richards give consistently hilarious, unsympathetic performances.

Under different circumstances this might make more sensitive audience members uneasy. However, the white masks recall the minstrel tradition so pronouncedly that it makes us comfortable with the ethnic humor and highly comic depiction of Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, especially given that Dauzvardis and Richards play the youngest and most vulnerable of the Scottsboro boys. White actors made fun of blacks for years in minstrel shows playing on stereotypes and prejudices and the minstrel influence on vaudeville can clearly be seen in Stein’s play, Menendian’s direction, Richard, Arzell, Dauzardis, Harvell, Malone, and Miller’s performance, and Knezz’s mask design. It is hard to deny these black actors the opportunity to do the same as minstrel performers, particularly as they simultaneously play the emotionally draining role the black characters who suffered under the machinations and racism of the powerful white men and the false, and often lethal, allegations that racism bred with grace, depth, and compassion.

Ultimately, Michael Menendian’s superb direction ensures that we experience melancholy, quiet outrage or, at least, frustration, humor, tragedy, and the vaudevillian tradition simultaneously during a compelling and linear, if non-traditional, narrative which balances comedy, pathos, tragedy, and vaudeville all the while maintaining a unity of tone and theme: sorrow and injustice. One of the most powerful aspects of the show is the way in which Menendian has blocked it, moving the actors across the stage in and out of pronounced but effective lighting (Diane D. Fairchild) that constantly varies in color, mood, and intensity. Together, the incredibly artistic shades of lighting and the actors’ movement through it, are beautiful, elegant, and meaningful. It must have taken a great deal of coordination between Menendian and Fairchild, but it pays off for the effect is spell-binding. The consequence of such gifted direction is that the play, though often funny and containing numbers from the light-hearted genre of vaudeville, is gripping, haunting, and intelligent so that we experience all the intensity, tragic beauty, lyricism, sadness, and high drama that so routinely grace the Raven’s stage.

Direct from Death Row: The Scottsboro Boys (An Evening of Vaudville and Sorrow) runs through November 14th, 20015 at the Raven Theatre, located at 6157 N. Clark Street. The Nearest El Station is the Granville Red Line. Performances are Thursday through Saturday at 7:30 pm and Sunday’s at 4:00 pm. Regular Tickets are $42 dollars. Senior tickets are $37 ($3 discount if ordered online in advance) Student, Teachers, and Military tickets are $18 ($1 discount if ordered online in advanced). Groups of 10 or more are available for Thursday and Friday Performance at $21.00 and for Saturday and Sunday performances at $25.00. To Purchase call 773-338-2177 or visit www.raventheatre.com. Limited Free parking is available in a lot adjacent to the theatre and free on-street parking is available nearby.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-up and click at “Direct From Death Row”

More Stories

“Two Sisters and a Piano”

“Hamilton” Reviewed by Paul Lisnek “Curtain Call Chicago”

“In Pursuit Of”